While the decline of the West is by now a well entrenched narrative in both Europe and North America, it is chiefly on this side of the Atlantic that the decline has a feral aspect to it. Europe still pays homage to its faded glories and exerts its muscle memory to go through the motions of pretending to have a civilization. Here in North America, that old game of charades is over. You can straighten up your act, get an education, a job, and pay your taxes, but this is largely for the sake of barricading yourself into a comfortable house or an apartment, turning on Netflix, and forgetting about the indignities of the street. Common areas have turned into dead spaces. Voters can only imagine civility and order being preserved through the strong arm of the law.

A general vibe of decay and lawlessness has become the norm. It seems particularly acute in this country, which has traditionally considered itself more peaceable than its southern neighbour. Canada’s crime severity index increased in 2023 for the third year in a row. There were particularly notable increases in extortion (+35%), robbery (+4%), and assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm (+7%).

Under our current right-wing drift, extra policing and private security are presented as the only viable responses, while liberals seem to have no response at all. In Alberta, the number of private security licenses issued or renewed by the government has skyrocketed, up to 19,270 licenses in 2024 compared to 14,583 in 2023 and 13,298 in 2022.

In Alberta’s biggest cities, some apartment buildings have already proven unsafe enough that property owners have hired private guards to attempt to keep the peace. Tragically, two of these security guards have been killed since December 2024. In Calgary this March, 73-year-old George Fernandez was killed while attempting to prevent a parcel theft. Just before Christmas of 2024, Harshandeep Singh was shot and killed while working as a security guard at an apartment building on 107th Street in Edmonton. Singh was the second security guard to be killed in Edmonton in 2024. There were also three guards injured while attempting to remove a man carrying a knife in the Stanley A. Milner Library, a place frequented by a large number of families, including my own.

J.G. Ballard published High-Rise in 1975, the year I was born. The novel opens with its protagonist, Dr. Robert Laing, sitting on the balcony of a suburban high-rise apartment, eating a dog, reflecting on the “unusual events” that have occurred in the building over the previous three months. The high-rise to which Laing retreated after his divorce seemed to provide everything a prosperous urban denizen could possibly want, including a gym, swimming pools, a restaurant, and high-speed elevators. Yet after power failures and minor grievances between neighbours, the high-rise became the scene of increasingly lawless behavior. The different floors were stratified according to social classes, and these different classes waged battle against each other. The basic functioning of the building failed and yet no one ever moved out.

This is close to Lord of the Flies territory, but with even more ominous implications. William Golding’s masterpiece supposed that children, when returned to a “state of nature,” would devolve into some sort of Hobbesian war of all against all. Ballard’s account of the behavior of adults forces the reader to confront the possibility that degeneracy isn’t some prospect facing us on a faraway desert island. The brutality with which the major characters of High-Rise treat each other offers no comfort to cosmopolitan readers—the middle-class denizens of leafy surburbs like mine. It is no accident that in Ballard’s book the violence and depravity are perpetrated by educated, cultured professionals.

It is easy to read High-Rise as a dramatization of concepts pioneered and popularized by Freud and his successors. Beneath the repressed exterior of every human there is a seething undercurrent of desires and urges that, when unleashed, lead to mayhem and violence. That could be the basic theory that High-Rise dramatizes. But Ballard generally does not look inward. He casts his lens externally and notes the effect of the environment on the behavior of humans. For the most part, the facts aren’t inspiring but unsettling. Humans are like ants. They have created a structure for their lives that doom them to move around in ways that appear to be totally senseless.

The future, says Ballard in an interview, is most likely to resemble Las Vegas. The tourists come with their pocket money and engage in exactly the behavior that the casino proprietors and architects have devised for them. The tourists have no more sense to them than ants. For hours they sit at Texas Hold ‘Em tables or video lottery terminals, in a state of over-stimulated wakefulness, their most committed movements being to the washroom to relieve themselves, or to the buffet table to feed. Outside, in the merciless heat, those who have given up, having lost their way and their livelihoods, drift around the city without purpose. Over fifteen-hundred of them reside “off the grid” in tunnels burrowed deep underground. They steal and stab with a casual indifference toward others, or they open up with disarming vulnerability, blurting out their most harrowing stories, finding human connection even in the nightmare of existence.

In an hour-long video released in October of last year called “They Ruined My Hometown - Don't Let This Happen to Yours,” videographer Peter Santenello tours Burlington, Vermont. This was the third Santenello video I watched and the first that documented the life of a town with which I have a passing familiarity. My first visit to Burlington was on November 4, 2008, for some canvassing work with the Obama campaign. I had the opportunity to shake hands with Bernie Sanders, the town’s former mayor, who was that year supporting the Democratic campaign. I made several other visits to town over the following ten years, usually with my wife. We would typically dine above our pay grade, walk down to the lakefront, talk to the friendly locals and relax. The compactness and walkability of Burlington’s downtown, the conviviality of the residents, the general aura of politeness and neighbourliness, the spectacular views of Lake Champlain and the surrounding hills—all that made a lasting impression on me. Santenello’s video, therefore, came as a bit of a shock.

Santenello starts off walking down Church Street and enters a business called Homeport, a family-run store that sells pretty much everything. The shopkeeper tells Santenello that theft costs his business about $75,000 annually. Traditionally, the shopkeeper was able to stop would-be shoplifters at the door by asking, “Did you perhaps forget to pay for something?” All that ended one day when a shoplifter shoved him violently and shouted: “What are the police going to do?” That’s when the shopkeeper hired a security guard. From Homeport, Santenello continues to wander downtown, talking to the owner of a mechanic’s shop, originally from Lebanon, as well as a landlord, originally from New York, and both of these small business owners fill his ear about theft, drug use and crimes, petty and not so petty. One of them hollers, “I’d pay the National Guard to come in here right now and clean this place up.” Every now and then, Santenello turns his camera toward a church, on the steps of which are transient people, buying or using drugs. He never actually talks to any of them.

Santenello talks to a woman business owner. She tells him about having witnessed a homeless man stab another homeless man in the neck with a pair of scissors. She also tells him that she once saved the life of a woman who was overdosing, injecting her with Narcan, which reverses the effect of opiates. But once the drugged-addled woman had been saved, she was angry, arguing that her high had been ruined and that she was now going to have to do another trick in order to get high again. Last, Peter Santenello enters Decker Towers. This is when the video presents an unforgettable scene that I think Ballard would have found intriguing.

Santenello’s tour guides are Cathy Foley, a 68-year-old trans woman who many years ago served in the United States Marines, and a younger man who goes by the name of Mike, and who sports a T-shirt that says THAT’S WHAT I DO: I FIX THINGS AND I KNOW STUFF. Decker Towers is a property run by the Burlington Housing Authority that offers low-rent accommodation to the elderly as well as people living with disabilities or mental illness. Santenello is escorted first to the lounge on the top floor which is ostensibly for the use of residents, with exercise equipment, tables, a washroom, and a huge window offering a fine view of the lake. The lounge had been off limits to residents for many months because intruders had on a nightly basis entered and locked the door behind them, using the facility for bathing and for the ingesting of drugs. On the floors below, the laundry rooms and the rooms for recycling and garbage had also been frequented by intruders. They ripped apart the tops of the washing machines to get at the coins inside and tore out the internet routers to sell for drug money. The stairwells, meanwhile, were covered in urine, feces and needles. Cathy was elected chair of the building’s first ever tenant council and helped lead the fightback against its occupation, making numerous complaints to city hall, to the property managers, and to the police. She came to be aware that as many as eleven drug dealers were living in the building. One day, two of them threatened her life and so she upgraded from carrying bear spray to carrying a pistol.

Santenello’s camera lands on the local newspaper. “You made the front cover!” he says. The paper is Seven Days and the article is called “The Fight for Decker Towers: Drug Users and Homeless People Have Overrun a Low-Income High-Rise. Residents Are Gearing Up to Evict Them.” The article enters some of the minutiae of the bureaucratic and political wrangling behind the attempt to bring order to the chaos. The Burlington Housing Authority asked the City for $600,000 to support hiring two security guards who would patrol the building around the clock for a year. The city baulked at the absurd cost and said no. The mayor disparaged the housing manager for talking smack about the cops. When the housing authority realized the sheer scale of the drug problems in the building, they installed Narcan in the hallways, over the protests of the residents.

By the time Santenello got to the building, the stairwells had been cleaned up, and common areas, such as the eleventh floor lounge, had been returned to the residents. Yet Cathy’s optimism was tempered with realism. The warmer months are always easier, she tells Santenello, because outdoor encampments are still habitable and the building gets far less use from outsiders. In the inhospitable cold of winter, it’s quite a different matter. She is bracing herself for a return of the rough sleepers and the “trouble-makers.” The previous winter had brought a continual stream of varied woes for residents:

Over the past few weeks, someone defecated in a hallway recycling bin, and the stench permeated nearby apartments. A vandal or thief ripped the door to a resident-run food shelf off its hinges. Someone tried to cut through a $600 steel cage installed to shield residents' packages from thieves. Laundry machines were ripped apart. In the parking lot, within view of surveillance cameras mounted on a mobile security trailer, a car windshield was smashed. Seven Days

It’s not premature to whisper a sombre eulogy for the political force that birthed the current conditions. Liberalism is a zombie ideology. That is to say, it is dead, and devoid of any greater purpose beyond perpetuating a simulation of itself. Patrick J. Deneen’s scathing indictment, Why Liberalism Failed, lays bare many of our contemporary societal tensions. Tracing the lineage of the word liberty in the book’s opening, Deneen argues that in the tradition of the west, it has meant self-governance, that is to say, the difficult feat of achieving self-rule given the continual threat of base appetites to a harmonious life. Under this traditional conception of liberty, a person can (and should) successfully rule themselves without any coercion from the law. That is to say they should be expected to curb their own worst impulses and to nurture the better angels of their nature. Yet liberty evolved over time and arrived at almost the opposite definition from where it had started. The liberal subject is now an individual who is free to do pretty much whatever she likes, provided her behavior doesn’t violate any codified law.

This conception of personal liberty aligns with economic liberalism, which helps to explain why it has been so successful. “Fulfilling the sovereignty of individual choice in an economy requires the demolition of any artificial boundaries to a marketplace,” explains Deneen. Whether we are considering a human subject or a corporation, the goal is always freedom. Yet we are now so free that only an ever-expanding set of rules will work as a restraint (since it’s in the natural order of liberalism that each individual entity seeks to do whatever they want). Whatever floats your boat is the adage that lubricates our society. Whatever maximizes profit is the motivation that greases the axles of our economy. Old customs are seen as antiquated, a brake on progress—a constraint on liberty—and hence are to be demolished.

Liberalism has purported to serve human interests well for decades but in recent years, as its refusal to concede to constraints or social norms has bordered on the perverse, the edges of this internally contradictory ideology are starting to become torn and tattered. The pandemic should have been a proving ground for the robustness of our prosperous, liberal society, and while there were hopeful signs that we would collectively get our act together, the ultimate verdict on this era of history will not be positive. Why should individuals who were raised to believe that their own liberty is the highest good submit to vaccination mandates or lockdowns? Why shouldn’t free liberal subjects get their news and medical advice from whatever source they please, including Joe Rogan or RFK Jr? And, indeed, why shouldn’t someone in the grip of intergenerational trauma, desperate to ease the pain of poverty and mental and physical ailments, be free to nod off to fentanyl in the middle of the town square—provided they are not hurting anyone else? If that’s how they want to live, who is anyone else to judge? It is not the job of the liberal state to offer up negative opinions of such people. The state purports to be neutral, looking to reason and evidence to guide decisions. For the liberal state, it is only upholding contracts and enforcing the law that count. So if you want the town square to be free of transients, you’ll have to pass some kind of law banning their presence.

We have reached a stage of liberalism that claims to be compassionate and yet is very cruel, in which almost every life choice can be validated, but as soon as you collide with the letter of the law, or with the ruling ethos of liberalism itself, the state can be stiflingly oppressive. Narcan saves lives, long live Narcan! Even in places where the locals don’t want it! You better not tear the Narcan dispenser off the wall. That would be against the law. Yet passing out in the stairwell after defecating in your trousers—that’s something we’re going to have to let slide.

In the story of Decker Towers, we are confronted with liberal principles as they show up in real life. Liberalism—as it erodes the commons, increases inequality, removes constraints on anti-social behaviors—puts city residents face to face with some very real situations. Many city residents are starting to distrust the platitudes spouted by their rulers. They are very susceptible to the right-wing while being increasingly hostile to the left—or whatever is the infernal force that currently passes itself off as a left nowadays, which does not take crime seriously and finds it quaint that bourgeois families no longer want to witness suffering, psychotic breakdowns and open drug use in public spaces.

Yet the question of urban blight in high-rises, town squares, and back alleys isn’t exclusively a political one. If it’s in North America where western decline has become truly feral, that is perhaps because what we have on this side of the Atlantic is an infrastructure of the void.

Standing at the intersection of 82nd Avenue and 91st Street, the homeless man hollers with rage at the sea of passing motorists, some of whom might perhaps give him a curious glance if they even notice him at all. I swear, I feel just one really bad week away from joining that man in his hollering, because what is the function of the intersection? It is designed to alienate. It’s an intersection that is saying to anyone outside of a vehicle: you are not supposed to be here. Everywhere in North America, this form of infrastructure predominates. Almost nowhere can humans simply be. That’s loitering. Everywhere humans must be engaged in purposeful behavior, and then they must move on.

The lesson from Ballard is to attend to the external drivers of behavior. Since our liberal, technological society offers up so little meaning and so much ugliness, we have increasingly become meaningless and ugly people. Cities have to give people more reason to leave their homes than merely earning and spending money. What we need is an infrastructure of virtue. What is that? I don’t know exactly, but it’s surely situated somewhere between our two current extremes. At one extreme there’s the bland primness of suburbia, where the obsession for ownership reigns, and where almost nothing of interest ever happens, and if it does happen it’s a matter for the law. At the other extreme is the total debauchery of skid row.

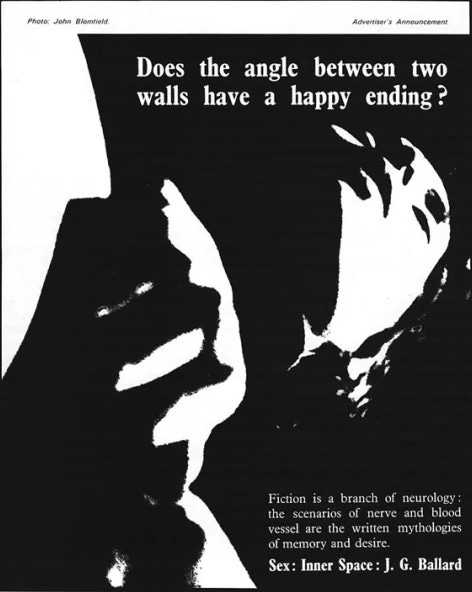

The angle between two walls doesn’t necessarily have a happy ending, but it should bring us closer to the light.

NOTES

Did any of this resonate?

Thanks!

This is the penultimate post from the Substack Octopus before going on a long summer break! The next post will be a sequel to “Shadow Work.”

Articles, videos

Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2023, The Daily, Statistics Canada, July 25, 2024

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240725/dq240725b-eng.htm?indid=4751-1&indgeo=0

J. G. Ballard, “The Art of Fiction No. 85,” Interview with Thomas Frick, The Paris Review, Issue 94, Winter 1984

“They Ruined My Hometown - Don't Let This Happen to Yours,” Peter Santenello

“The Fight for Decker Towers,” Seven Days, Derek Brouwer, February 14 2024

https://www.sevendaysvt.com/news/the-fight-for-decker-towers-drug-users-and-homeless-people-have-overrun-a-low-income-high-rise-residents-are-gearing-up-to-evict-them-40200776

“The Visitor: An Interview with J.G. Ballard,” Hardcore Magazine, 1992

https://www.jgballard.ca/media/1992_hardcore_magazine.html

“Inner Landscape: An Interview with J.G. Ballard,” Friends, 1970

https://www.jgballard.ca/media/1970_oct_friends_magazine.html

"Numb at the Spectator summer party," Sam Kriss, July 9, 2023

“I Visited The Hidden Tunnel Community of Las Vegas,” Drew Binsky,June 29, 2024

"Security guard killed on job in downtown Calgary made ‘countless sacrifices’ for family, says nephew," Mackenzie Rhode, Calgary Herald, April 10, 2025

https://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/george-fernandez-family-mourns-death-calgary-security-guard-amanda-ahenakew

“A security guard was gunned down in an Edmonton apartment building. His death is drawing attention to a risky, rapidly growing industry,” Johnny Wakefield, Edmonton Journal, December 9, 2024

https://edmontonjournal.com/news/crime/edmonton-security-guard-killed-jobs-industry-murder-homicide

Images

J.G. Ballard, “Does the Angle Between Two Walls Have a Happy Ending?” Ambit 33 (Autumn 1967). Retrieved from Andrew Gallix

https://andrewgallix.com/2015/10/04/does-the-angle-between-two-walls-have-a-happy-ending/

My wife and I live in a rough neighbourhood in Toronto. Some of this rings true, some of it less so. We were out of the city for a year-ish, and on our return we noticed that the people smoking hard drugs on the street had skyrocketed. Beyond the number of homeless people, you do see far more "kooky" behaviour on the streets than you did in 2019. That said, it's pretty rare that we feel actively menaced/fearful for our person or property. The vibes are not nearly as bad as in downtown Edmonton.

I don't feel any animus towards the homeless--the passerby is not the party who's really suffering. But past a certain point, I don't think you can expect people with a higher sensitivity to disorder not to get upset. I just don't really know what a solution looks like in the short-medium term. Using the cops doesn't accomplish much other than moving people around, at high cost to the pubic & the people moved. I lean towards housing first, but that still takes time, and I have little faith in the city to implement it quickly & competently. And it seems like you'd still be left with the "trouble-maker" streak you mention in the article, an anti-social core that messes things up. Maybe the new drugs are the problem, but escalate-the-drug-war doesn't sound promising, and whatever the merits of safe-supply, it's not obvious that it calms people down and BC shows the politics are impossible.

As a left-lib I'd quibble about the relationship of "liberalism" to this, but regardless, the situation is a bummer and doesn't appear to be getting fixed anytime soon.