Development: “the rearrangement of the environment in such fashion that space, time, materials and design favor production and consumption while they degrade or paralyze use-value oriented activities that satisfy needs directly.” Ivan Illich

Few experiences present as many instances of shadow work as modern-day travel. You visit the websites of Canada’s two major airlines to book a return flight from Montreal to Vancouver. You’re eager to find out if you can redeem some loyalty points from WestJet but the website is of no help so you spend forty-eight minutes on the phone only to find out that the flight you’ve chosen is not eligible for the points program. Grumpy and resentful, you nevertheless book the flight. On the eve of departure, you follow a link to check in online. Then you print your tickets. It’s quite possible to fly without paper copies simply by showing the electronic versions, but your seven-year-old phone has not been great at holding a charge lately and the last time you were in the airport it was a hassle to get a seat near one of the highly coveted charging stations.

You reserve an Uber on your phone. When the Uber arrives, it becomes clear within three minutes that the driver, who immigrated to Canada nine weeks ago, does not know how to get to the highway without ensnaring you both in a traffic tailback caused by the roadworks that afflict your local artery. You provide him with step-by-step directions on taking the alternate route and manage to lose only about five minutes of precious time. At the airport, you remember to get your phone out again, tip the driver and rate him a charitable four stars—hating the very idea of a rating system and how it has stealthily infiltrated so much of life, creating a society of snitches.

Inside the airport you go to the appropriate electronic kiosk, enter your flight details, and watch as a baggage ticket is coughed up quickly. Separating the sticker from the backing with your cold, dry fingers is a painstaking affair that makes you feel like perhaps you are the clumsiest and most inept person to ever enter an airport. It takes two minutes to accomplish the task. You hand over your suitcase to a WestJet attendant and then you join the long line that snakes in coils at the entrance to security. A sign overhead indicates that the average wait time to clear security is twenty-seven minutes. You get out your phone yet again and scroll through emails, noticing a message that was sent by WestJet saying that your flight is completely full and the airline is looking for volunteers to check in their carry-on luggage. Well, I’m not doing that, you think privately. All I have for carry-on is this small bag for my laptop and notebook, which is half the size of some of the other bags I can see in this infernal queue.

Once it’s your turn to be hassled by security, you know the drill. You remove your belt and shoes, take your laptop out of its bag and place it in its own tray alongside your phone, and take off your coat and blazer, and place those on top of your shoes in a separate tray. The walk-through scanner does not beep when you pass through it, which is a relief. You wait to be reunited with your belongings on the other side. Not far away is a multi-generational family. Their two-year-old has just thrown his Paw Patrol backpack onto the floor and dashed away toward Starbucks, and his father is running after him, shouting. Ahha, Starbucks, you think to yourself, as your first tray emerges. As you get on your belt and blazer and retrieve your electronics from the second tray, you keep eyeing Starbucks. It is, as of this current moment, mercifully free of a long line-up. I can’t wait to get my hands on a mediocre coffee and a highly fattening slice of banana bread, you whisper to yourself, almost loud enough for people to hear you. The encroachment of shadow work has started to make you feel like you might be going mad, the result of which will be that eventually, like Dostoevsky in a previous century, you’ll walk around the city constantly muttering to yourself angrily.

You get zero pleasure from your flight.

Readers of Karl Marx have probably encountered the terms use value and exchange value. The former refers to the practical use of a good that meets a person’s needs directly. The latter refers to a commodity that can be traded on the market, once it is assigned a price that indicates its value relative to other goods. There is an overlap between use value and exchange value. That is to say, the same item can be both.

During the pandemic, many people procured all the ingredients they needed to bake bread at home. In so doing, they created an item with a use value—a tasty, nourishing loaf that could be devoured by the residents of the household. If, however, the same household members were to open up an industrial-sized oven, hire a baker and teach him their special recipe, and if then they take the baker’s loaves of bread to the market, selling them at a profit, they are trading a commodity with an exchange value.

The development of our society to this point has meant the gradual replacement of use values with exchange values, until the latter come to dominate the former. If you have to spend money to get a benefit that used to be free or could be obtained simply by dint of your own freely given labour, then you’ve probably fallen prey to our commodity culture. My favourite example of this is urban travel. If it were possible for me to get to most of the places I need to go to in Edmonton by walking or cycling, my travel costs would be extremely low. A century ago, most residents of a city would not have considered the cost of getting around to be a major drag on their household income. But now, with the requirement for households to have one or two vehicles, simply getting from A to B can be very expensive. You have to go out on the market and try and find a car that is dependable and safe. Then you have to register and insure the vehicle, and you need to fuel it, and you have to keep up with maintenance. All this to get around in an area that, in theory, should be walkable or cyclable. How much more pleasurable it would be to walk in a city without traffic, hearing the birds sing, feeling the vibrancy of the elements and the relationship of your body to the wind and the surrounding buildings. In such a city, you would actually be able to think.

This is not a state of affairs that our overlords want.

Shadow work is a further drag on our freedom and happiness. Under the increasing dominion of shadow work, life is no longer simply a matter of putting in time at a job in order to earn the money needed to procure the necessary commodities to sustain life and carve out a morsel of joy or contentment. There is now a third demand on your time, straddling obstinately the space between work and leisure. I picture it as a rickety bridge. You cannot participate in work unless you’re prepared to pass over it. Yet you cannot entirely be at ease and enjoy your leisure time if the arches of the bridge are perpetually in your peripheral vision. You have to pay a very real mental toll to the bridge as you pass over it countless times each day.

On just a few occasions, my wife and I have hired a cleaner to help bring order and cleanliness to our home during periods of time when we’re simply unable to keep up. I always say that the very best thing to do after the cleaner has done their labour, and the home is as presentable as an art gallery, is to take the kids out to play and to then eat dinner at a family restaurant. When you come back at bedtime, the house is still in its pristine state and you can prolong the feeling of pleasure at the orderliness of it all for just a few hours longer. In this scenario, money is spent on the outsourcing of shadow work.

Craig Lambert’s book, Shadow Work, published in 2016, defines shadow work as “all the unpaid tasks we do on behalf of businesses and organizations.” Lambert says that shadow work has slipped into our lives stealthily, and most people do not realize how much of it they are already doing. Unlike regular work, shadow work hours are seldom counted up. If a shift starts at nine o’clock and ends at five with an hour for lunch, that’s an easily countable day of seven work hours and one hour of paid downtime. But the commute is not paid. The app you had to download to access necessary software before you even showed up at the office—that’s not paid either. What about the long detour taken to drop off the kids at school? What about the fifteen minutes you spent preparing their packed lunches? Is education compulsory in our society? Yes it is. Do kids need to physically get to school and do they need to eat at least one meal while they’re there? Yes they do. Yet increasingly, what is compulsory becomes the sole responsibility of individuals, and is not provided for by society. So shadow work eats up more and more time and yet is hardly recognized by mainstream discourse because most people don’t have a name for it. Is four hours spent volunteering at the casino so your child’s school can buy Chromebooks an instance of shadow work? Personally, I think it is. Is cleaning a house—another of the examples provided above—shadow work? Given the way our society is currently structured, with a need for workers who can pop out of their homes every day, adequately fed and hydrated and not crawling with lice or fleas and smelling like refuse, housework is almost definitely one of the vital bridges we must pass over to get from leisure and employment and back again.

Four forces have driven shadow work to its current prominence. Technology is at the top of the list. Who needs a travel agent to book their holiday when there’s Expedia? Are supermarket cashiers truly necessary when the customer can use a self-serve check-out instead? The democratization of expertise is another driving force. Do you need to hire a lawyer to write up a will when you could download a template and do it yourself? This democratization is constantly propelled forward by a third force—the ever-expanding realm of information. Millions of YouTube videos now explain to you how to conduct simple household tasks like changing a faucet or the filter in the humidifier. Lastly, changing societal norms help pave the way for more and different forms of shadow work. Offices used to have small armies of secretaries to help perform all manner of tasks. The steady decline in the number of secretaries, who were almost always women, can lead to awkward workplace dynamics. White-collar men and women uneasily eye the empty coffee pot or the pile of dishes in the sink. Who will tackle this unglamourous shadow work? (There used to be thousands of YOUR MOTHER DOESN’T WORK HERE signs from coast to coast to coast, until those were removed, relics from an age of motherhood that scarcely exists anymore.)

Lambert devotes considerable time to fleshing out examples of the encroachment of shadow work, employing a breezy, narrative style. The history of self-serve gas stations, for example, takes us to Winnipeg, Vancouver (the sites of some of the early self-serve gas pumps) and beyond. He takes a brief detour to discuss how women eventually became convinced that pumping gas was something they could and would do, and also examines particular cases where some female voices spoke out against this development (the pumping of smelly, dirty gas should remain a man’s task, these voices proclaimed).

The chapter dealing with childhood is one of the most striking. Lambert sees the encroachment of shadow work in education. Parents become increasingly involved in day-to-day tasks that should primarily be the preserve of the paid teacher. He remembers a time when parents would say goodbye to their kids at the doors of the yellow school bus and have zero involvement with classroom activities for the remainder of the day. Those days are over. Schools are recruiting parents to help with homework, to be volunteers, to read with their children every morning, a state of affairs that generally favours affluent families where books and know-how are abundant. Yet few families can resist this kind of work. The social pressure is enormous. Lambert argues quite convincingly that when parents hover over their children to this extent, they are eroding the accountability that every child should be developing toward their teacher and toward their various duties.

Lambert comes down even more harshly on the cult of organized sports that has gripped North America in particular—baseball, hockey, soccer, and so on. Organized sport has largely replaced informal playtime in the streets. Decades ago, kids would organize their own sport activities, make their own rules, bring their own equipment, etc. I still remember this disappearing world. In England, my friends and I would get together to play tennis, go for walks, practice skateboarding, and so on. Upon moving to Edmonton, I can remember one winter participating in shinny hockey at the local ice rink. There were no adults present at any time. The worst thing that happened is my friend took a slapshot toward the goal and my helmetless head happened to be in the way. I was rushed to the local clinic for four stitches. It was a memorable experience.

Shadow Work, published by Illich in 1981, is very different from Lambert’s book of the same name. Illich works quite overtly in a tradition informed by Marxist thought, and the terms use value and exchange value underpin his eloquent description of the disappearance of things that used to be free. We’re back to the example of the motorized vehicle:

Up to now economic development has always meant that people, instead of doing something, are instead enabled to buy it. Use values beyond the market are replaced by commodities. Economic development has also meant that after a time people must buy the commodity, because the conditions under which they could get along without it had disappeared from their physical, social or cultural environment. And the environment could no longer be utilized by those who were unable to buy the good or service. Streets, for example, once were mainly for people. People grew up on them, and most became competent for life by what they learned there. Then streets were straightened and reshaped to serve vehicular traffic. Ivan Illich

Competence and self-reliance are themes that recur in Illich’s writing. He values these qualities to such an extent that at a certain point I could almost feel him decisively parting ways with the Marxist tradition. There is a lot about the modern world that elicits Illich’s skepticism, suspicion and disdain, whereas Marx was absolutely a creature of the Enlightenment, and championed progress just as enthusiastically as any modern-day techno-futurist weirdo.

Illich, a devout Catholic and an anarchist, is always conscious of the good things from the past that capitalism has destroyed. One of the more significant losses is access to the land.

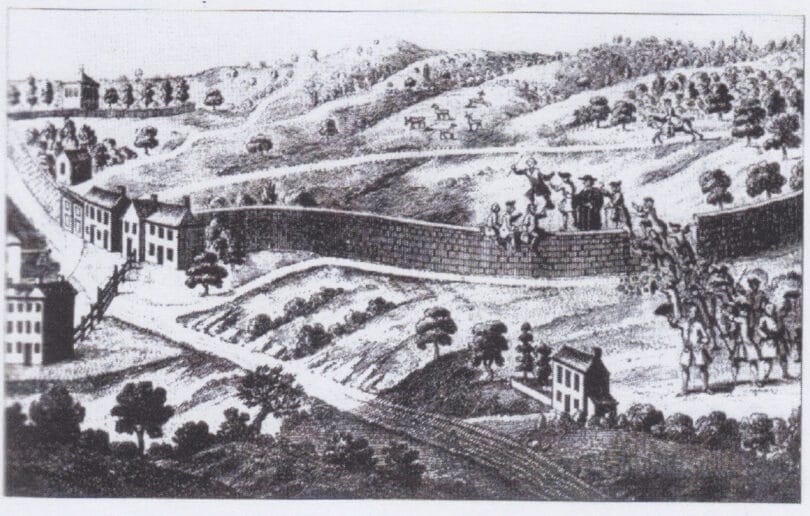

If capitalist elites are to successfully create a society in which they can enrich themselves through the selling and trading of commodities, it is vital that a large number of people be deprived of self-sufficiency through the process of the intentional fracturing and ultimate destruction of their direct relationship to their traditional means of survival. Britain’s Enclosures Acts provide the template for this historic shift, which has been enacted in diverse ways throughout the world everywhere that capital has made its unceremonious appearance, always with the same result: household sufficiency declines, wage labour increases. An army of landless former peasants and serfs—or even yeomen and skilled trades people—eventually find themselves set loose in a new world, freed from many of their former attachments and duties and yet with new obligations that prove to be just as coercive in their own way. They now owe their living to a capitalist system and have nothing to sell on the market but their labour.

Wage labour has numerous social implications, not the least of which is the fact that wherever and whenever it is introduced, no one very much welcomes it. Well before the total triumph of industrialization and capitalism, our ancestors understood that wage labour represented a fraying of the normal attachments and protections of traditional society. Writing about Florence in the 14th century, Illich observes: “the need to provide for all the necessities of life by wage work was a sign of utter impotence in an age when poverty designated primarily a valued attitude rather than an economic condition... The dependence on wage labor was the recognition that the worker did not have a home where he could contribute within the household.”

Wage labour also casts into the shadows its opposite: unpaid labour. Whereas previously, every member of the household had their part to play and no form of work took priority over any other, wage labour pulled the men away from households and into industrial production. This left women to shoulder the burden of domestic work alone. Domestic work was the first form of shadow work. Not only did this historical development consign women to a form of labour considered lesser—because it came without wages and wasn’t in any way a measurable part of capitalist production—it also disrupted the status of the household as a discrete economic unit.

As comedian Steven Wright once said, “If you think nobody cares about you, try missing a couple of bill payments.” Money makes the modern household. There is no other input more crucial than regular injections of cash. This position of dependency upon the money economy has torn men and women away from prior social formations. It has been worse for women than men because the power they formerly held as members of a self-sufficient household was eroded and they became economically vulnerable—in many cases their plight became little better than that of children.

The shadow work performed at home sometimes consists of the exact same chores as those of earlier eras—whether cooking, cleaning, or caring for children. What distinguishes it from earlier forms of domestic labour is its relationship to capital. In a self-sufficient household, all chores are for the betterment of household members. Under capitalism, the exact same chores are a necessary prerequiste to production, trade, and the replenishment of the stock of labour.

It is now, in the 21st century, very clear that the rise of shadow work is yet another force that erodes “the commons.” From the Enclosures Acts on, history seems to rhyme. First we lost the land. Then we lost the streets, which were emptied of people and became the territory of motorists paying high prices for the privilege. Under shadow work, motorists pump their own gas, and so they are deprived even of the human company that used to come at full-service stations. DOMO’s slogan was “we jump to the pump for you.” The gas attendants did not jump, exactly, but they did sometimes exchanges some pleasantries about the weather or the price of petroleum. Even urban travellers who use public transport are increasingly driven toward self-service. You can no longer go to the convenience store or pharmacy to buy bus tickets. You order a transit card online and load it up with rides the same way. In countless small ways, shadow work means the decline of human relationships, which were part and parcel of common spaces. It makes modern life feel sterile, hyper-individualistic, and devoid of charm. As Illich observes, perhaps detecting the limits of his own capacity to adequately describe the powerful forces he observes, “Prose cannot do justice to a social organization set up to enlist people in their own destruction.”

NOTES

I will be coming back to the topic of shadow work in a future installment.

Books

Shadow Work: The Unpaid, Unseen Jobs That Fill Your Day. Craig Lambert. Counterpoint Press, April 2016

Shadow Work, Ivan Illich. Marion Boyars Publishers. January 1981

Photos

The Conviviality of Ivan Illich (Part III), O.G. Rose, October 9, 2023

https://o-g-rose-writing.medium.com/the-conviviality-of-ivan-illich-part-iii-9b3b017f2ed0

“Against enclosure: The Commoners Fight Back”

https://mronline.org/2022/01/19/against-enclosure-the-commoners-fight-back/

Illich and Jacques Ellul are my favorite critics of industrial society.

wondering when I can make the time to sort 38,000 unread emails