I expected a long night. My instructions were to present myself at the Century Casino on Fort Road at ten minutes to eleven and proceed to the Cash Cage. There I was to assist with the counting of cash through to three-thirty in the morning. The expected attire was “business casual,” and the text message had told me in no uncertain terms to refrain from alcohol or gambling for the duration of my shift.

Refraining from alcohol—that was a small sacrifice. Refraining from gambling—that was no sacrifice at all. Decades ago, when I was a teenager, I was sitting next to an older gentleman on the plane, and he told me I had a lucky glint in my eye. He gave me two dollars and insisted that as soon as the plane landed I should use the gift to buy a lottery ticket. I betrayed his trust and purchased myself a chocolate bar instead.

My ongoing abstention from gambling makes me an outlier in Alberta. Seventy-two percent of Albertans over 18 engaged in at least one gambling activity last year. The same year, Alberta distributed $1.43 billion in revenue raised through bingos, casinos and video lottery terminals. This money was dispersed among Alberta charities, which includes non-profits in schools, daycares, after-school programs, arts organizations and even churches. The province's legislated approach to gaming as a charitable activity is unique in Canada.

Only once has anyone made a big fuss over Alberta's Faustian bargain with gambling. In 2006, Bishop Fred Henry of Calgary wrote in his pastoral letter: "The School Board, the individual schools, and related parent councils and societies must get out of bingo and casino gambling fundraising activities.”

The backdrop for this dispute was the austerity agenda that the then-premier, Ralph Klein, had imposed during his first term. By 2006 there was a modest reinvestment in schools but tax dollars alone were insufficient to support the range of activities that educators and parents wanted to provide for students. Fundraising became the expected supplement to regular revenues. Bishop Henry had told Catholic Trustees in 1998, “You’re assuming that fundraising is normal. It’s not. It’s an aberration. …[It’s] simply downloading the problem on the individual schools and school boards.”

The Trustees of Calgary’s Catholic school board eventually decided to get out of the gambling business, forfeiting about $2 million in annual revenue. But the rest of Alberta’s school districts, as well as the charitable sector generally, remained hooked.

My own volunteer efforts at the casino were in support of my eldest daughter’s after-school care program. When I write the words, “after-school care” I feel that a prior version of myself, a non-parent, would have barely had the patience to read the rest of this. After-school care sounds like an extra, an option. Almost seven years into the parenting mode of life, I now know that such programs cannot be considered an option. What else is my child to do when the school day ends at 3:30pm (2:30pm on Thursdays)? What is she to do on professional development days when the school is closed? She has two working parents. After-school care is a necessity for us, just as it is for so many others.

Outside the Cash Cage, we volunteers formed a small group. We had never met each other. I was pleasantly surprised how quickly a good humoured camaraderie formed between us. After showing the official casino staffer our IDs, we were given nametags to wear, each one bearing a security code number that provided access to the counting room. We also had access to a side room, a sort of lounge, where we were allowed to sit, talk and drink coffee or tea while we weren’t counting money.

The real work didn’t begin for an hour. During that down-time, we went to the casino restaurant and ordered a late-night dinner. We didn’t have to pay for anything. I was a little uneasy about tucking into a meal having not even worked a minute, and yet I was also curious to know my fellow volunteers better. Everyone turned out to be progressive, affluent, and educated. There were a few handwringing-style comments about the election of Trump. One of the volunteers was a high school chemistry teacher, which inevitably teed up references to Breaking Bad. He fielded these comments with the world-weary air of someone who has heard it all.

Another of the volunteers was a pathologist at a local hospital. She told us that her son, aged only sixteen, had figured out a way to run the data from patients at risk of breast cancer through a special program he had coded on his computer. His home-crafted program appeared to be just as good at calculating the risk of full-blown cancer as the expensive tests that local labs are obliged to procure from the United States. The pathologist was applying for grants to support scaling up the home-grown solution.

At midnight, we filed into the counting room. As with the entire casino, there were no windows. Yet unlike the garish, multicolored, blinking and flashing lights of the main playing area, the counting room was austere. It was a little bit like a police interrogation room. There was bright overhead lighting and a large security camera. Each of us had an assigned role. Two volunteers were at the head of the counting table. Their job was to open the metal boxes of money from the casino tables, and then sort the money into the appropriate denominations, using a plastic tray with dividers. Hundreds here, fifties alongside, etc. My job was to take these trays and start feeding the bills into the counting machine. Afterwards, I would read out the numbers to the volunteer sitting directly next to me, who entered the information into a computer. Across the table from us were two volunteers who performed the exact same functions as us. After counting the take from each money box, the two pairs of counters and data enterers would compare the totals to check if their figures matched.

The first cart of money was rolled into the room by two armed security guards just after midnight. Watching the proceedings was a thin, blond woman—a casino staffer. She was well advanced in years and told us that she was still working so as to ensure that her husband, a retiree, could “live the lifestyle to which he has become accustomed.” We were also watched by an official employee of the Alberta Gaming and Liquor Commission, who stood in a corner, a laptop resting in the crook of his arm. He didn’t do much typing or talking. He had the right kind of demeanour for the job—serious, humourless, vigilant.

A stack of hundred-dollar bills, several inches thick, has an aura. I thought that exposure to so much money would make money banal, but the truth is I didn’t work for long enough for the banalisation process to unfold. When I had a stack that was considerably bigger than the counting machine could handle in one go, I stood up, as if out of respect. In my mind I was thinking, this actually is a little bit mad.

The take from each casino table varied, from a low of $3,000 to a high of over $70,000 from a Texas Hold ‘Em game. The counting machines got jammed up sometimes, rather like a Xerox copier would. These were rather deflating moments, as the momentum of the rapidly ascending numbers came to a halt temporarily. The staffer would trot over amiably and help inspect the machine, opening it up if necessary. Sometimes the counting machine would eat as many as five bills, and a delicate extraction process was required. I was grateful that Canada’s currency had been switched over a decade ago from paper to polymer; otherwise there would have been many torn bills.

On a washroom break, I overheard one young man talking to another about a strategy he was successfully deploying at the lottery terminals. Being unfamiliar with all the games, I didn’t know how to interpret his strategy, but it struck me that the basic human instinct for gambling hasn’t changed much over the years. In 1863, Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky was in the spa resorts of Wiesbaden, Bad Homburg, and Baden-Baden in Germany. He was in the grip of his gambling vice. But he thought he had things under control, as this letter to wife’s sister testifies:

Please do not think that, in my joy over not having lost, I am showing off by saying that I possess the secret of how to win instead of losing. I really do know the secret — it is terribly silly and simple, merely a matter of keeping oneself under constant control and never getting excited, no matter how the game shifts. That's all there is to it — you just can't lose that way and are sure to win.

One of Dostoevsky’s lesser known novels, The Gambler, was written to pay off his gambling debts. Aside from the introduction of new flashing gizmos, I don’t think Dostoevsky would have been all that surprised at what he would find at the Century Casino on Fort Road in Edmonton.

During a break in the waiting room, I pointed out to my fellow volunteers that no other province relies on gambling revenue the same way Alberta does. The pathologist, who originally hailed from the United States, said that gambling is illegal in her home country unless it’s on land that is run by Native American tribes. Another volunteer said quite bluntly, “There is no other way to raise so much money so quickly. Think about it. Are you going to raise this kind of money through a bake sale? Selling cookies door to door?”

The high school chemistry said: “This is the social contract in Alberta.” He didn’t follow that up with any other statement. There was a mood of awkward resignation to the status quo.

Back in the counting room, we did a second count, our last before the end of the shift. The counting machines chattered obediently. I gently tapped stacks of cash against the metal table in an attempt to make them neat and tidy, handing each one over to my counterpart on the other side of the table. The high school teacher, after opening each box and emptying it, would make a big show of presenting the emptied-out box to the security camera on the ceiling. This was part of the required protocol. Every bill, and even the rare toonie or loonie or quarter, had to be accounted for.

The total amount of cash we counted was over $290,000. I cannot report exactly how much of that will go to my daughter's after-school program. The allocation is determined according to a formula that averages out casino earnings over a three-month period, divided up among the participating organizations. Last time around, the after-school care program sent volunteers to the casino for two consecutive nights, the same as this year, and netted $75,000.

When we volunteers were finished, we drifted our separate ways. I walked back to the silent parking lot. The vehicles of the gamblers who had been in the casino for many hours were becoming encased in ice.

I turned on the engine of my humble Hyundai and turned onto Fort Road, which, even at close to four in the morning, was still resplendent with electric light, especially Belvedere LRT Station. At the periphery, darkness creeped in from the vast industrial zones and the not-yet developed swathes of rough prairie grass. I was surprised to find myself quite awake, not depleted. The work hadn’t been difficult.

The following morning, at my daughter’s ballet class, operating on less than five hours of sleep, I went into the office to ask for the wifi passcode, and the amiable staff person said, “How are you doing?” I explained that I had put in a shift at the casino and that I was a little underslept. The staff person smiled immediately. “Oh good, you’ve done your duty for the year then!”

Alberta's unusual gambling model relies on a strange form of social solidarity. Volunteering at a casino is the civic duty of a responsible parent, or so we are made to believe. There is also, undeniably, an element of gentle coercion. At my younger daughter's pre-school program, parents who fail to volunteer at a casino lose their deposit. In our case, that's $1200.

This is gambling at an industrial scale, enthusiastically sanctioned by the state with the mix of regulations and incentives that you would expect from any other form of economic activity. Don't think about the harms associated with gambling—the suicides, the lies, the evictions, the bankrupted families, and so on. If we went back to Alberta's more principled stance of the past, when gambling was prohibited for religious reasons, we would forfeit the revenue and doubtless pay more taxes to make up for it. Yet that is a price I would gladly pay. How about a modest provincial sales tax to make up the difference? But I suspect I am in the minority. At this moment in history, a new sales tax would be as popular as smallpox.

And so the casinos remain open. Vice thrives where sleep is scarce. At the strange hour that my volunteer shift ended, normally I would be waking up in my own bed. I drove home, untroubled by traffic. I felt that I had performed one of my few Alberta rites of passage. I woke up a few hours later with a headache.

Notes

“Who Wants Albertans to Gamble More?” Evan Ostenton, Alberta Views, October 1, 2023

https://albertaviews.ca/who-wants-albertans-to-gamble-more/

“Activists fight video gambling in Calgary,” Deseret News, February 13, 1998

https://www.deseret.com/1998/2/13/19363244/activists-fight-video-gambling-in-calgary/

"Board and bishop clash over bingo," CBC News, June 23, 2006

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/board-and-bishop-clash-over-bingo-1.601880

“Alberta Set to Follow Ontario’s Lead in Regulated Gambling Market,” SEGEV LLP, August 13, 2024.

https://segevllp.com/alberta-set-to-follow-ontarios-lead-in-regulated-gambling-market/

“Alberta wagers allowing more online gambling operators will capture illicit market,” Joel Dryden, CBC News, September 3, 2024

"Fyodor Dostoevsky Life, Gambling Addiction, Roulette," Greg Walker, March 20, 2021

https://www.roulettestar.com/people/fyodor-dostoevsky/#letter1

Photos

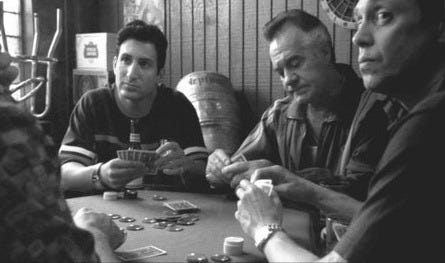

On the set of "The Sopranos," Season 5, Episode 9

https://www.imdb.com/media/rm1695390976/nm0218318

The other photos are mine.

This is insane… I had no idea this was the model in Alberta. It’s shocking what we are able to accept as normal just because we let it happen for a long period of time.