Here at the Substack Octopus, we’re having fun launching a new project with an old friend, Jinwoo Park. Introducing Translate This!, a conversation about books in translation, with a heavy focus on books translated from Korean or French. We hope you enjoy our conversation about The Vegetarian by Han Kang. This is the first of what we hope will be a recurring feature, and as we keep going, we aim to deliver better and better production value. Feedback and suggestions are warmly welcomed.

You can listen to our conversation below or read the transcript that follows.

LAURENCE

Well, this is the inaugural episode of Translate This! which is a conversation about books in translation. And joining me today is Jinwoo Park.

JINWOO

Hello. Okay, so I'll just introduce myself briefly. As he said, my name is Jinwoo Park. Excellent pronunciation, by the way. And yeah, I was born in Korea. I moved to Canada when I was 11, and I lived in Vancouver, lived in Long Island, of all places. I lived in London, and now I'm in Montreal. I am a writer. I have a debut novel coming out this September called Oxford Soju Club. Just happy to be here to talk about books in translation, because that's also what I do. I also do literary translation as well.

LAURENCE

That's a fantastic introduction. My name is Laurence Miall, similarly a writer, similarly someone who's traveled around a bit, lived in the UK up to the age of 14, then moved to Western Canada, in Edmonton, specifically, and then lived in Montreal for 13 years, and that's where you and I met and have been friends ever since. Now we've launched ourselves into this crazy adventure of having this conversation, hopefully on a semi-regular basis, about books in translation. And I think we're going to be reading a lot of Korean books. I think we'll be reading a lot of books, French books in translation. I don't think we'll limit ourselves just to French or Korean, but I think that because of where we come from, that's likely to be a lot of what we talk about.

JINWOO

And not to not to mention, Korean books are in vogue right now, thanks not just to the Nobel Prize win this year by Han Kang, someone that we're going to be talking about later on as well. But just in general, the strength of Korean culture at the moment is at its zenith. I feel like literature is definitely benefiting from that as well, which is great to see because if K-pop leads to people reading Korean literature, I'm all for it. I love K-pop, but it's like my thing is that, hey, if you like this one thing from this country, then don't shy away from exploring the other stuff. Why are you only sticking to this? You know what I mean? That's right.

LAURENCE

If you're going to get down with “Gangnam Style.” I'm dating myself here. Get down with all of it. Yeah, exactly.

JINWOO

If you're going to get down with Parasite, the film, then check out everything else. Come on. Don't stop there. Yeah, exactly. Where do you think the film culture comes from? The literature. Always encourage people to explore culture in a more holistic way. That being said, I also need to practice that as well. But I mean, having said that, I think also I have a heavy amount of interest in Japanese literature, as well as I'm trying to get into more like Filipino literature at the moment because there's a lot of interesting stuff happening there, though a lot Filipino literature is not a translation because they write in English.

LAURENCE

Interesting.

JINWOO

But also interesting other Asian literature, like out of China and other European literature as well, among the numerous languages.

LAURENCE

We're going to go everywhere. We're going to go everywhere, yeah. I think the main rule of this show will be we're not going to talk about books by the Anglophones that everyone's heard of like J. K. Rowling or Dan Brown. So this is Translate This!

And as you've alluded to, Jin, the first book we're going to discuss today is The Vegetarian, and you've got a beautiful copy there to hold up. The Vegetarian by Han Kang, who won the Nobel Prize in 2024. I just finished reading this book on Wednesday at the cafe, and there was a bit of an annoying conversation happening in the background that kept interfering with my enjoyment of the final 20 pages. But I managed to finish and thoroughly… enjoyed is not the right word for this book. But I want to turn it back over to you because this was your pick, this book. Why don't you tell everyone a little bit about it and why you picked it?

JINWOO

The novel itself is a very simple novel to introduce. It's basically what happens to a family when this woman decides to become a vegetarian. It really just comes out of the blue. She just decides to renounce meat and she won't go near it. She won't accept it. I believe she also rejects her husband because he smells like meat.

LAURENCE

That's a memorable line. “You smell like meat.” That was a buzzkill.

JINWOO

It's certainly a buzzkill for the husband. The thing is, this is one of the most visceral books I've ever read in my life. Not because of just how weird or strange it really is. It's very reminiscent of quite a bit of magic realism that pervades the South American literature space. But also it's packed with that social commentary that is very typical of Korean literature, especially more in the literary spaces, the non-genre spaces. If you don't know much about Korean literature, much of it is dominated by anti-government commentary because Korea used to be a raging dictatorship for half a century. So literature naturally became the focal point for resistance movements, whether they were actual resistance, like the protests or more intellectual resistance, for which people also went to jail for. People used to go to jail for reading the wrong novels.

LAURENCE

So it happened. Would Han Kang ever have fallen into that category?

JINWOO

She did get blacklisted by the government in early 2010s for her other book called Human Acts, because that book dealt with the Gwangju Uprising, which was a violent crackdown of civilian protests by the military where hundreds died and thousands were hurt. Basically, she wrote a book about it, and the government in... I think it was around like 20... It was just on the cusp of her Booker Prize win. She had her... Her works and her name as a writer, they were blacklisted unofficially by the government because this blacklist came out when they investigated into President Park’s government in 2016. It came out that her and numerous other writers were on a blacklist where they were not able to receive any grant funding. They were exempted from being promoted internationally for book fairs and book festivals. Any government support was taken away from them with various agencies, including the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, being pressured into not supporting these authors.

LAURENCE

I've noticed there's a lag between this book—I mean, there's quite often a long lag between the original of any book and it appearing in translation—there's a bit of a lag with this book. I forget how many years. I think this initially came out in three installments and then collected as a novel that then appeared in English a few years later. Did this book get caught in the crossfire of that?

JINWOO

I mean, it recently got caught in the crossfires of a book censorship in Korea for having graphic sexual content. Because as we know, that does happen. It's in the second story, I believe. Also, there is, and this is trigger warning, there is sexual assault in this.

LAURENCE

Everything about... I mean, you said visceral. I mean, graphic is another... This is a short novel that is psychologically complex, but it is at times unspeakably violent. And this, I guess, is something that literature can still do, that if films do it, I mean, there are certain scenes in this book that feel like they would be unfilmable. You couldn't screen this level of cruelty. Yeah. Walk me through a bit why you feel with the huge reputation that Han Kang has, that you felt that you and I, Jin, should start with The Vegetarian, because I'm going to straight up and say, obviously, I'm the tourist here. This is only the second Korean novel I've ever read, and my first Han Kang novel. Why start with The Vegetarian?

JINWOO

I would say when you start with Han Kang, I would say you start from either of two books. One is Human Acts and one is The Vegetarian. I usually direct people towards Human Acts because it also helps to understand the Korean psyche in a way. Human Acts is a book about the violent government brutality upon its civilian population. It's a bit of a microcosm in itself of how the government treated its people over a half a century in Korea, all the way from 1945, when the country was liberated and promptly taken over by the US military government. But in my opinion, The Vegetarian has also these very literary qualities that are quite poignant once you get past the surface-level weirdness. For example, the idea of a woman's rebellion, just her way of existence being accepted or not accepted. In this case, it's very vehemently rejected. That is a commentary on how the women's movement has been received in Korea. We see a lot of these very surface-level legal and policy-level improvements that have happened over the years. But many times the attitude is still very conservative, and women are not treated equally in Korea.

It's one of the big reasons why birth rates have declined. If you look at things like, try to think of it this way. Anytime a woman says, “I am not going to do this,” and it goes against the conventional norm of society, that's what this book is trying to do. For instance, now that women in Korea are saying, “We don't want to have children. We don't want to get married.” This is the analogy here, essentially. I think it's very significant in that sense because it goes beyond the Korean context. It goes beyond the very Korean history and cultural background. This is a universal struggle, a universal struggle of daring to be different. Do I have a right to exist as a different person? When it's refused, what do you do? How do people react? The answer is that people react very violently.

LAURENCE

Yeah. Well, I mean, this is... Obviously, the premise is deceptively simple. The woman, Yeong-hye, and you're going to have to constantly correct me on my pronunciation.

JINWOO

You're good. You're good. Yeong-hye.

LAURENCE

Yeong-hye decides to stop eating meat. It's a deceptively simple premise. But she has been set up as being the most ordinary woman through the eyes of her husband. And I think that this was really a clever way into the novel because we are seeing her through the eyes of her husband who's never found her to be remarkable in any way. Just a really steady, unassuming person who makes him breakfast every morning and sends him off, and he works very long hours, comes back late. Her refusal to eat meat is apparently the influence of a dream. At this point, I'm like, Oh, is this going to get really weird? Is this going to take me to places where I'm not going to fully understand it because we're going to be purely in the realm of metaphor here? Not eating meat, does it mean something else? But in fact, it really does mean she's not going to eat meat. I think that the point at which the novel had me completely is when the husband has his formal business dinner with his colleagues, and wives are supposed to attend. And she attends, and she won't eat meat. It's a big deal. It never stops being a big deal.

JINWOO

And I think that's why it works so well, because you replace meat with anything else, and it still works. Won't wear a bra, won't wear high heels. Even the most insignificant things suddenly become a ground-breaking, earth-shattering offense when a woman does it. I think that's what it's trying to say in many ways. It's like, look at what is happening to us. Look at what you do to us. Yeah, you think this is ridiculous and this is weird, but this is our reality. I think that's why also I really like this book because I recommend Human Acts if you want to know more about Korea in itself. I recommend this if you want to know more about Han Kang's literary world, the way she writes. Because also in her simplicity, there's also a lot of poeticism in it. She started out as a poet, actually. Her other books are quite poetic. For instance, her book, The White Book, is essentially an amalgamation of poetry and prose. But in this case, this is a book that transcends borders, transcends cultures. I think every culture can say, yeah, there's this thing that women don't want to do anymore. It's weird, but it's the most harmless thing. Who are you harming? Who is anyone harming by not eating meat?

LAURENCE

It's interesting that the first... And just to talk about the book structurally, there are three parts, and each one is told from a different perspective. This is a technique that I have rarely been on board for. I'm going to just admit that in my very idiosyncratic way. The shifting of the point of view can be a bit brusque, and it can be difficult to follow the connecting thread, but Han Kang does this incredibly well. The first two parts are both from the perspective of men. The first one is her husband, the second one is her brother-in-law. And because we only get a woman's point of view at the end with her sister, in a sense, we've spent so much time looking at her through the male gaze that there's a lot about her that's been minimized and objectified. And I just wanted to go back to you, Jin, in terms of, is this typical of how Han Kang works? And what does it say about where men are in all of this? Are they actively resistant to women showing individuality in any way? Or is this a top-down thing that requires the government to enforce it?

JINWOO

I think it's a system thing, first of all, because it's about power dynamics, partly, because at the second, through the interactions of, and this may be a bit of a spoiler, so a warning, but through the interactions between Yeong-hye and and the husband, so In-hye's husband, and Yeong-hye, through their very dramatic interactions, who is… And their equal consequences, or as in their They're equally consequential in the way that they both meet consequences. Who meets the worst consequences? It's the woman. It's power dynamics, partly, too, in that men, even when they act in accordance with, act with risk and stuff like that, they still have less to lose. That's one part, in my opinion. But the other part is that men, in this, under the current systems, men are also at a position where they can potentially… They can easily take advantage of people who are trying to change. They can try to… That they're at a position where they can easily try to exploit people who are getting rejected for their changes.

LAURENCE

This is what the brother-in-law does. This is purely an exploitative relationship for his own amusement, really.

JINWOO

Yeah. But he packages it in a way where, yeah, I am doing this for art. I'm doing this for this seemingly greater power and calling. I think it is also a statement on a lot of male allies in the feminist space, really, who later turned out to be just to be in to exploit things for their own benefit. We have seen people. Those kinds of people have been called out, but it's just the way it is. I think it shows It's almost a minefield that a lot of women have to walk through in order to accept themselves as well as be themselves and express themselves in their own way in the world. I think the closest person who comes to understanding her is her own sister, because she is also a woman who has had to be a provider as well. She is a provider in the family.

LAURENCE

Can I just say that neither of the men in this novel ever looked like they could ever be a provider or a decent father? I mean, I don't think I'm speaking out of turn to say that. You and I are both fathers. You are raising a young boy. I'm raising two girls. I looked at both of these men in this novel. I'm like, You guys... I mean, one of them doesn't have kids, right? But the one who does, I mean, he's just a complete absentee dad through and through. There's no spoilers in just saying that. And yeah, I'm wondering, what do you think of all this?

JINWOO

So one side of it is that I view it through the Korean lens, which is that the Korean society is very patriarchal and especially combined with their Confucian roots. A patriarchal Confucian society is one where men are allowed to be absolutely useless but still have value.

LAURENCE

That is well said. Yeah. The video artist, who is the brother-in-law, seemed to me especially useless because he would retreat to his studio for hours and hours and hours on end with the expectation that he was going to produce some amazing work of art, and he rarely, if ever, did.

JINWOO

Yeah. I think that's one critique of it. I agree with this, too. For so long, and I mean, obviously, this doesn't really apply to the newer generations, but for so long, men did not have to prove their worth. Men simply existed, and by existence, they were proven of their worth in Korea. Whereas women had to constantly prove their worth. They constantly had to prove that they were worthy of being in the family. It was not uncommon, even until the recent modern times or pre-modern times, where women would be driven out of the family if they couldn't conceive a son. Yeah.

LAURENCE

That is a heavy, heavy burden. I mean, there's this quite a famous case, hundreds of years ago, of Henry VIII who for a long time couldn't conceive a son, and it was considered to be a big deal. But we're just talking, we're talking about almost a medieval country at this stage in development. So that is quite, for that dynamic to continue up to comparatively recently is quite something.

JINWOO

So I think it's that commentary and that critique displaying this way where we're seeing these two absolutely horrendous and useless men having a perspective on this woman. That's the thing, too. The value of the woman is now being judged by these men. It's not being properly measured by, well, we're not properly measuring who she is on her own terms, neither are we allowing her to even have a voice. That's something that is also a part, is part of the commentary. It's the fact that the value of these women are being set by these useless men who have never known how to prove themselves in the world.

LAURENCE

Before we wrap up here with this discussion of what is, honestly, I mean, that's why I felt we should have a series devoted to books in translation, because our culture is still dominated by Anglophone books, and I find often that books in translation are far more interesting than your average book coming out of the United States or UK or Canada. Would Yeong-hye ever really have been noticed at all if she'd not chosen to be vegetarian and then gone a little crazy in the eyes of everyone around her, the men, especially around her?

JINWOO

Yeah. I think that is also a significant point. If she had remained invisible, yeah, no one would have batted an eye at her or anything. But that's the other thing, too. Women, if they're not crazy, like bat-crazy, they're relegated to the back. But also women who are excellent are also relegated to the back. Case in point, her sister. She's an excellent woman. She's a very productive woman. She does everything she can to save and salvage the situation. She's an excellent mother, it seems to be as well.

LAURENCE

She's an entrepreneur. She's a businesswoman. She, in a sense, seemed like almost a superhuman, in that there is so much that she is capable of. And yet it feels like she's always going to be relegated to some secondary position.

JINWOO

Exactly. I realized at some point, perhaps that this character was representing the Korean mothers that had come before, the ones that were holding up the generation of women who are now trying to change things, trying to say no to things like Yeong-hye. I think that's also why she's the one that resonates with her the most, because they share this bond of being women, just in this sense of sisterhood. I think in a way, that's how I view the book: that the family is a microcosm of Korean society. It's a microcosm of Korean society marred by collective trauma, marred by all of this marginalization of half of the entire family, which are the women, and the unfairness that pervades it. I think over time, this is a common experience, I feel, which is that a lot of dads just don't do anything in the household, and it's the mom that has to do everything. But it doesn't also mean that the mom doesn't work. Korean mothers would often also work and earn a living, if not solely by themselves. Because like I said, for the longest time, Korean men did not have to prove their worth.

They could just exist, and they could go out and drink, and they could take another girl brazenly and just come back to the family at any point. This was the case. There's another book called Please Look After Mom by Shin Kyung-sook. That more viscerally paints a portrait of what Korean mothers went through in many cases. Not to extend this discussion for too long or dwell in this space too long, but I think if you can frame it that way, that's where the book really takes off in seeing these family dynamics as something more than just a family dynamic, but as a social dynamic that extends outside of the family boundaries.

LAURENCE

Yeah. Well, thank you so much for walking us through this book. As we go through this series, we're going to be changing perspective. We launched the series with The Vegetarian, which is your pick. I'm going to pick something that... I mean, the bar is high because this was really an incredible book. But let's go there. We start with the bar very high. Thanks, Han Kang. Thanks to you, Jinwoo. And we need some signature trade sign-off for this show. I'm not quite sure what it should be. Maybe we should take listener suggestions on this. But for now, I'm maybe going to say: Everyone have a wonderful intro to 2025, insofar as that's possible. How would you like to say goodbye to folks on this inaugural show of ours?

JINWOO

Well, since it is the new year, I will say, Happy New Year. Happy 2025! I hope everything great happens in the midst of all this terrible stuff. And go read a translation, please. That's all I will say. Very well said.

LAURENCE

So with that, everyone have a good one. We're going to wrap up this inaugural installment of Translate This! and we will be back soon with another fantastic book in translation.

JINWOO

See you later.

NOTES

Next up on Translate This! we’ll take a look at A Man’s Place, by Annie Ernaux, another Nobel Prize winner.

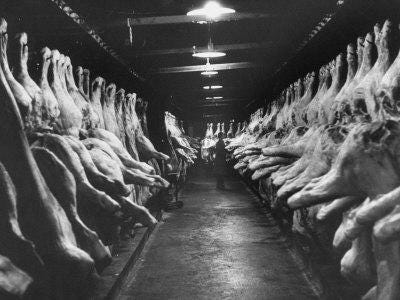

Photos

Sides of Beef at Les Halles Market

https://www.art.com/products/p15543115-sa-i3787105/sides-of-beef-at-les-halles-market.htm

“South Korea's Han Kang wins Nobel Literature Prize,” Annabel Rackham, October 10, 2024. BBC News

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c206djljel1o

Love the format, super engaging and now I want to read Korean novels…