Surviving Canada

Margaret Atwood, Heritage Mall, FUBAR II, Billy-Ray Belcourt & the Tawatinâ Bridge

When I first moved to the Prairies, people kept raving to me about the sky. “Look at the sky!” they would say. “It’s incredible. There is no sky like the Prairie sky!” For over twenty years I refused to heed these people. Privately I thought: What you’ve done here at ground level must make you ashamed or leave you indifferent if you’re telling me to wrench my eyes away from what's right in front of me and stare at the useless sky!

I had immigrated at the age of fourteen with my parents to the southwest quadrant of Edmonton, which was then, as it is today, inhabited primarily by wealthy homeowners for whom access to a two-car garage is a right. On my first full day in Canada, I was told that Heritage Mall was an interesting place to visit. Coming from rural England, I was excited about the proximity of a shopping facility where there would be lots of people. I crossed the north-south artery of 111th Street and trudged across a vast and mostly vacant parking lot until I arrived at a store called Woolco. My confusion increased as I entered the store and quickly found what I needed—new underwear and a T-shirt—but failed to find the mall. I’d been told there was a food court, a fountain, an atrium, and two floors of stores basking in natural light that streamed through glass skylights. But I had no idea how to navigate my way to these splendours.

“That’s it?” I said to myself, deeply underwhelmed and confused. “That’s the mall? That’s one of Canada’s interesting places?”

Until recently, I felt rather alone with my underwhelmed and confused feelings, which expanded from Heritage Mall to include a good number of other places. Yet slowly, especially in my forties, I have uncovered key texts that help deepen my understanding of my adopted country. (The texts will be of little use when it comes to Heritage Mall, all retail leases having been terminated in 2001, the buildings demolished, the land eventually birthing an even more confusing and incoherent place—Century Park.)

One of the key navigational texts I want to look at today is by the Canadian author whose reputation looms over all others—Margaret Atwood. I don’t turn to her out of any particular fondness or because I think she offers the indispensable guide to our country. Her appearance in this Substack is the result of a chance encounter. As I was working on a totally different project with totally different aims, I came across a quotation from Atwood, went to the primary source, and thereupon became immersed. Something shifted in my mind.

In the early 1970’s, Atwood surveyed Canadian literature, looking for our national mythology. The result was Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature. Atwood argued (convincingly, I think) that the overarching symbol in Canadian literature is Survival, or La Survivance. In countless literary works, Canada is a terrain in which the chief task of the individual is simply to get through it, endure, ride out the storm, hold on until morning—survive, survive, survive.

Historically, the obstacles to survival are external (lethal cold, lethal Nature, lethal unknowable vastness), and the rewards of surviving are meagre—i.e. you survived, what more do you want? In literature of later periods, the obstacles become internal and spiritual. Is it possible to survive as “anything more than a minimally human being?” Atwood asks. For French Canadians, survival meant “retaining a religion and a language...” Indigenous stories were almost entirely excluded from the canon at the time that Atwood was writing (more on this later).

Canada is a country in which the most important question any individual must ask is “Where is here?” It is not, as it might be in other countries, “Who am I?” The question, “Where is here?” is the necessary question because of the imperative of survival. “Where is here?” the Canadian must ask, as he looks around and tries to identify the rudimentary elements required for eking out some kind of existence. Before going much further, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the opportunity to continue surviving has been a fundamentally important one to generations of new arrivals whose prospects of survival were grimmer back home. So even if our national mythology underwhelms us (Atwood confesses that it underwhelmed her), at least it gives us something to work with, and we must be grateful for that.

“Where is here?” That’s our national question, and survival our national symbol. This is not the United States, where the national symbol is the Frontier: “a place that is new, where the old can be discarded… a line that is always expanding.” This is not Britain, where the national symbol is the Island: “island-as-body, self-contained, a Body politic, evolving organically, with a hierarchical structure in which the King is the Head.”

When Survival was republished in a fifty-year anniversary edition, Atwood updated her thinking to reflect the ongoing development of the Canadian canon. “Who am I?” had become just as important a question as “Where is here?” Yet I’ll admit to having little to no interest in that question. If it’s a question someone would ask in the United States or England, it’s a less quintessentially Canadian question.

On that drab day in 1989, I exited Woolco and started to walk around the perimeter of the mall, noticing as I did so that there was no sidewalk. The awkwardness of my situation continued as I kept close to the faux-brick wall for safety, just a foot or two from the occasional passing car. I turned the corner and saw Safeway. I entered and purchased some candy. I then walked home, occasionally glancing over at the so-called mall, which didn’t represent much. It looked like a half-dozen giant cardboard boxes that had been haphazardly discarded.

How to survive in territory like this, when boredom—a sense of lack, a feeling of confusion—is what must be endured? For city dwellers, which is to say eighty percent of Canadians, survival is not about confronting the frozen tundra of the North or a precipitous cliff drop in the Rockies or an encounter with a grizzly bear in the woods. Survival is the struggle in the core of our souls.

Atwood is very strong on this point and mines it for comedic effect repeatedly. Margaret Laurence’s classic work, The Stone Angel, is summarised thusly: “Old woman hangs on grimly to life and dies at the end.” Atwood also notices in Canada a strange attachment to the notion of failure and a “superabundance of victims.” Being a victim and failing to accomplish something are venerated national traits.

After my last three-thousand-kilometer drive on the Trans-Canada Highway (where Terry Fox famously failed to complete his cross-Canada run—cancer wouldn’t let him), I suddenly became perversely curious about the history of how this nation-building project came to be. It’s not an interesting history—the various federal-provincial haggles and deals that stitched together a patchwork of roads into a connected whole—but one overarching truth emerged: how miserable and arduous the day-to-day work of construction was for those on the frontlines.

Picture the men on the exposed crust of the Canadian Shield. The rock wore heavy scars, accumulated from millennia of glacial abrasion. The men put down dynamite and blasted that rock to smithereens. The December 1931 issue of The Rotarian described the government program that brought the army of surplus labour to work on the project. “How to operate the camps in the north during the heavy winter was a problem. Military methods were suggested only to be criticized by organized labour as well as the unemployed... Sanitary conditions of the best only could be provided to draw the least criticism and make the men feel they were not conscripted.”

This was one of Confederation’s defining moments—the sacrifices and suffering of the land and the people so that this flat ribbon of asphalt would permit drivers like me to glide along with so little effort that fatigue was one of our greatest challenges. Fatigue, of course, being potentially fatal. It all seemed very tough and grim. So much work, and for what?

My first friend in Canada told me a story that I have never forgotten. One day, he took the city bus to school, fell asleep, woke up, and realized he had glided past his stop. He got off and started walking south. But he fell asleep again—this time in the middle of the road. It was winter, he was inadequately dressed, and his body slipped into hypothermia. Fortunately an incoming driver—who also happened to be a teacher at his school—stopped in time, got out, and dragged his body into the warmth of the vehicle, saving his life.

I share that story because even in an ordered, suburban city such as Edmonton, the ever-present danger remains that the country will kill you when you’re just going about your business, doing nothing special. In England, dying would take more work or worse luck. Canada’s default mode is lethality—or, as Atwood more aptly puts it, “Death by Nature.”

Whether alive or dead the bush resisted;

Alive, it must be slain with axe and saw,

If dead, it was in tangle at their feet.

The ice could hit men as it hit the spruces.

Even the rivers had betraying tricks…

—E.J. Pratt, “Towards the Last Spike”

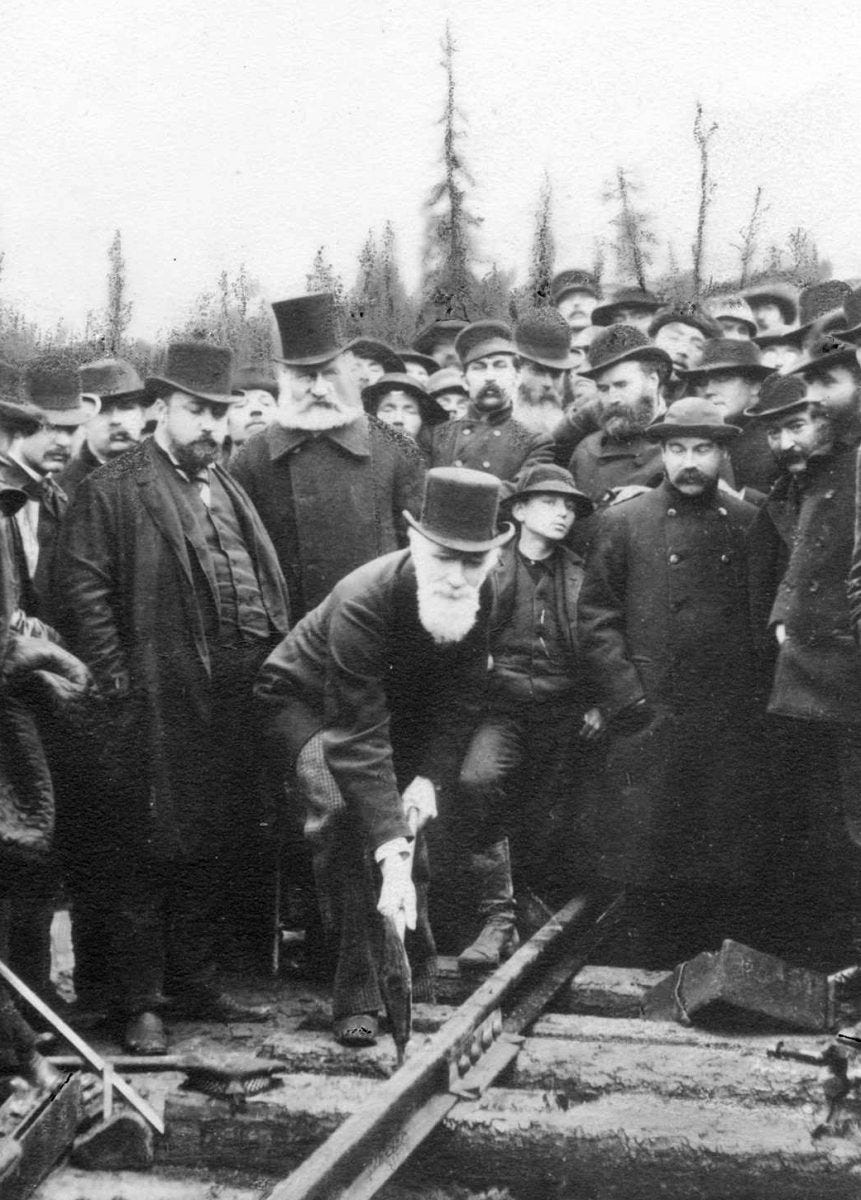

Nature has always been the traditional adversary of the settler. Canadian literature tells this story of conflict repeatedly. The Canadian Shield, well before the Trans-Canada highway was completed, became one of the key sites of an even more important nation-making project: the building of the railroad. In E.J. Pratt’s epic poem, the geological entity of the Shield—the oldest exposed rock you’ll find anywhere on earth—shows up as a dragon or a lizard, against which Prime Minister John A. MacDonald declares war. “She [Nature] fights back with the weapons at her disposal, namely the traditional ones of ice, rock and water,” is how Atwood summarises the struggle. To borrow some appropriate words from Northrop Frye, what’s going on is “the conquest of nature by an intelligence that does not love it.”

Allow me to jump forward, out of Survival, to a twenty-first century film, to argue in favour of the remarkable persistence of these themes. Many people instinctively laugh at me when I declare FUBAR II to be the most important Anglo-Canadian film ever made, but I am not joking. The story of Terry and Dean—classic hosers who, when the story begins, are financially at the end of their rope in Calgary—is of two men with no other aspirations but to earn a bit of money and keep on “givin’ ‘er”. Upon arrival in the infamous oilpatch of Fort McMurray, Terry and Dean’s meagre sporting attire is utterly inadequate to the severity of the coldness. So brutal is the work itself that Dean almost immediately gives up, resorting to the “worker’s comp hustle.” That is to say his buddy Tron (an oilpatch veteran) whacks him over the leg with a wooden two-by-four to cripple him so he will qualify for benefits.

Two particular moments from FUBAR II stand out for me. I’ll take them in reverse order from their appearance in the film. The first one hinges on the character of Tron, who is used to far greater effect in FUBAR II than in the original FUBAR. Here he’s gone feral. He’s lived in Fort McMurray long enough to embody the stereotypical traits of an oilpatch worker—that is to say, he is very rough in manner and speech and very hardcore about his drug use. He’s also an amateur rapper. In the bar at the end of day one in “The Mac,” Tron takes Terry and Dean aside and harshly whispers a poetic warning about the life they are in for up North:

The Mac, she's a cruel mistress, and she will freeze you, if you don't love her, the way we all love her up here. We are the Mac. Are you the Mac?

This is issued as a challenge. As the film unfolds, the threat of Tron’s warning never dissipates; it only intensifies. It seems very likely that both of these hosers will be unable to survive. Dean comes closest to the cliff of total despair, and Terry all but abandons him. If the film were not so ingeniously funny, you’d be chilled to the bone by the bleakness.

Earlier in the narrative, as Dean and Terry are driving north to Fort McMurray, they pick up a hitchhiker who turns out to be a hippie. From the back seat the hippie explains to his new companions that he’s headed to the oilpatch to do something about the plight of the ducks that keep landing in tailings ponds—those disgusting admixtures of water, sand, clay and residual bitumen left over from the process of separating oil from the muck. Tailings ponds aren’t good for ducks. Terry and Dean are completely unmoved and tell the hippie they don’t give a shit about the dead ducks—the world needs oil. They become sanctimonious. They ask the hippie this: how could he ever get to Fort McMurray were it not for oil? “Try walking a mile in the car’s shoes!” They throw him out at the side of the highway and steal his weed.

In just two scenes, FUBAR II exemplifies some of the most important attributes of the survival theme: the necessary submission to a harsh environment that threatens to kill you (Fort McMurray) and the freezing of the heart to Nature (ducks).

So I promised we’d get to the Indigenous presence in the canon. In the introduction to the anniversary edition of Survival, Atwood briefly notes the flourishing of Indigenous writers and poets. She notes that because there is so much Canadian literature in the 21st century compared to 1972—stories written from almost every possible perspective imaginable—a book like Survival would no longer be feasible. How could the sheer diversity be boiled down to one overarching theme like “survival”? Yet I think she’s a little too quick to dismiss the potential revelations a follow-up effort could provide. The presence of Indigenous stories alongside non-Indigenous stories illuminates both sides. Novels like Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot of the Seabird Island Band or the poetry of Billy-Ray Belcourt of the Driftpile Cree Nation are so completely different from anything that would have been attempted in any decade prior to 1972 that we should pause to consider what old ways may have been thrown into doubt and what new possibilities might have emerged.

On the Trans-Canada, roughly mid-point between Montreal and Edmonton—the span I know the best, if knowing that amount of vastness can really be done—there is a town called Thunder Bay. It has become quite infamous in large part because of the Canadaland podcast that described some of the town’s problems and characters in great detail. Overlooking Thunder Bay is a striking mesa called the Sleeping Giant. It is a large yet isolated flat-topped hill, which, last time I saw it, was keeled over on a cushion of radiant mist on Lake Superior. It is said that the Sleeping Giant is the remains of Nanabijou, the Spirit of the Deep Water, who revealed the location of a silver mine to the local Ojibway tribe under the condition that this secret never be shared with the white man. For many years the Ojibway enjoyed the beautiful artifacts they could make from the contents of the mine and were renowned for the ornate silver jewelry that they wore. But one day, a Sioux warrior, disguised as Ojibway, infiltrated their camp. Under false pretences, the warrior persuaded his hosts to reveal the location of the mine’s entrance. He subsequently shared this knowledge with the white man. When Nanabijou found out that the Ojibway had broken their promise to him, he lay down in the bay, crossed his arms over his chest, and was turned to stone, blocking the mine’s entrance forever.

I’ve spent an unproductive amount of time thinking about that story. The white man doesn’t make his appearance in these parts of Canada until around 1678. So I am tempted to ask: what was Sleeping Giant called before the white man came along? Several years ago, I had the good fortune of talking at length to the creator of the Thunder Bay podcast and, a day or two after our interview, I regretted that I had missed my opportunity to ask him for insights on this question.

Lately I’ve come to see my restless dissatisfaction with the original myth as a sign of my European heritage. Why the hell can’t I just accept the story? What is wrong with me? Receive the story and move on! It’s a symptom of a bad attitude to question a myth that is both beautiful, cautionary, instructive and that also perfectly explains the physical shape of the mesa which resembles a large man lying on his side.

Let me go further, into perhaps riskier territory. My attitude, which I am calling here part of my European heritage, is not mine alone, nor is it limited to a futile questioning of stories from other people’s cultures. In Survival, Atwood tells us that earlier generations of Europeans that came to Canada—in particular, the English—had high hopes that the country they “discovered” would conform to their Wordsworthian ideals of sublime beauty. The Romantic poet had filled their heads with appealing notions of the ameliorative and transformative powers of the natural landscape. What they found was not exactly that. The country let them down. The black flies and mosquitoes frequently made quiet contemplation impossible. The boggy land threatened to swallow them whole. The endless rows of trees drove them mad. The coldness and the big animals scared the hell out of them.

Here’s a poet of European-Canadian origin, Douglas LePan (1914 to 1998), whose work Atwood considers at some length. LePan’s poem. “A Country Without a Mythology” describes a stranger moving toward an unknown destination through an inhospitable land without monuments or landmarks. The Indigenous people are described as silent and moody, or if they do speak, they are “incomprehensible.” At length, we arrive here:

And not a sign, no emblem in the sky

Or boughs to friend him as he goes; for who

Will stop where, clumsily constructed, daubed

With war-paint, teeters some lust-red manitou?

Among Algonquian people, a manitou is a spirit that exists in all natural phenomena—animals, plants, geographical features, or the weather. In LePan’s poem, the manitou appears as a lust-red representation carved in the rock. The divine presence is in the land itself and yet, as Atwood notes, the eyes of the European poet do not linger there, because the divine presence is, according to his worldview, elsewhere.

The divine presence, for the European, is in the sky.

In the poetry of Billy-Ray Belcourt, even with its 21st-century vantage point, the separation between man and Nature is impossible. He finds Nature in his own body.

maybe if i surrendered myself to grandmother moon she would know what to do with these pickaxe wounds. there is so much i need to tell her about how my rivers and lakes are crowded and narrowing. how i managed to piece together a sweat lodge out of mud and fish and bacteria. she gives me the cree name weesageechak and translates it to “sadness is a carcass his tears leave behind.” (The Cree Word for a Body Like Mine Is Weesageechak)

If we Europeans have done very bad things in Canada, which at this point in history is probably incontestable, it’s perhaps a consequence of the fact that we refused to look seriously at the people and land that were right in front of our faces. We did not countenance their inherent worth, so blinded were we by the imperatives that brought us here in the first place.

Yet to this day, some of us have this annoying reflex, in tough times especially, to look heavenwards and not straight ahead. This instinct wasn’t in me at fourteen but it’s in me now—and I don’t think it’s only blindness or ignorance. It has been a response to conditions in which there appeared to be no meaning or law or obligation. The skyward glance or stare reveals an urge to say, “this world is not enough; it must be encompassed by another one.”

Since becoming a homeowner on the Prairies, I don’t need anyone to remind me to look at the beauty of the Prairie sky. Our house is tall, and the east-facing windows give us views of the morning sun. We see pink, crimson and burgundy. We see clouds on fire, clouds in nectar, clouds over ribbons of light and darkness. I can’t do the views justice, not with words and not with photos. The views are among the very best things to ever happen to us. My eldest daughter, from as young as four years of age, liked to pause to watch the stunning performances of that eastern light. That light pulls us away from what is going on down here, on the land, which more often than not is a dreary repetition of algorithmic patterns of human behaviour—streams of traffic, heads bent toward phones, solicitations for money.

About a month ago, on one of the last temperate days of October, I decided to walk from my downtown office to our home on the other side of the river. I wasn’t quite sure what my route would be yet I was convinced it would be easy enough to figure it out. Initially I was pleasantly surprised by the easiness of the walk. On the path beside the North Saskatchewan River I was one of several people enjoying the evening. There were couples, joggers, people taking photos, and when I crossed the Tawatinâ Bridge, on top of which the new Valley Line train was in the final stages of testing, I saw a man setting himself up with his saxophone and speaker and a collection cup.

On the other side of the bridge there were signposts telling me where to go, but I didn’t quite trust them. I didn’t heed the sign that directed me to the Mill Creek Ravine, which I can now see was a mistake. I kept on following the natural curve of the path I was already on until it took me to the Muttart train station, which was not yet officially open to the public. I was able to wander across the platform and to the sidewalk beyond. I kept on walking, thinking to myself: well, if this is the north-bound sidewalk that leads away from a soon-to-be-open train station, it must go somewhere useful. About three minutes later, the sidewalk quit on me and there was no other paved place to go except into Connors Road, which was full of cars and trucks. In other words, a pedestrian’s dead end. I might as well have been at Heritage Mall—doing everything wrong all over again.

In 1989, I eventually learned what I had done wrong. I had failed to push through to the far end of Woolco where the screen doors would have been open to let me into the main part of the mall. No signage had ever been installed to signal these directions. In 2023, it was far clearer what I had done wrong, and the solution was also very evident. I hopped over a fence, looked both ways to ensure no trains were coming, scrambled over the weeds and tracks, bounded up the slope on the other side, and found my way back to the pedestrian walkway. From the wrong, illegal path back to the correct one.

Several weeks later, the Valley Line officially opened. Those thirteen kilometres of tracks, from the southeast corner of the city to 102 Street downtown, are among the few in Canada that are dedicated to moving humans rather than commodities. In most of Canada, VIA passenger trains have to pull over into sidings to make way for trains carrying potash and grain.

That Monday, on a whim, our family walked down to the station at Avonmore and took the northbound train. When the train crossed the Tawatinâ Bridge we looked west, toward downtown and the setting sun. The towers had become silhouettes in the fading light and the sky beyond was bathed in a gentle glow. Never had the city seemed so beautiful to me—the dome of the legislature, the sharp slope of the river banks, the jagged edges of the human-built environment against the infinite space of the greying darkness—all these elements were in perfect composition thanks to the angle that the new train permitted.

I have chosen to remember that train ride as a brief glimpse at a possible future in which the point of Canada is not to extract maximum financial value out of its territory but to love it for what it actually is. As I watched my eldest daughter press her face against the window, having fallen silent, staring westward like almost everyone else, I was sure we were all doing something more than surviving Canada.

Notes

Heritage Mall: Further research has validated my feeling that Heritage Mall was a deeply weird idea. “The mall was advertised as being built to feel like summertime in Edmonton year-round. Its centre court was adorned with palm trees and waterfalls, and it boasted over 20,000 sq. ft. of glass, used in the building’s skylight.” This is what’s so deeply unsettling about Canada: a good number of its residents just flat-out reject the notion of Canada as a winter country. They want to be in Florida or California—anywhere else but here.

Book

Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature, Margaret Atwood. House of Anansi Press, 2012 edition

(all quotes and references are from this book unless noted otherwise)

Essay, articles, poems:

“From Parking Lots to Palm Trees (And Back Again): A Look Back at Heritage Mall”

“Canada Finds a Way Out,” James Montagnes, The Rotarian, December 1931

“The Cree Word for a Body Like Mine Is Weesageechak,” Billy-Ray Belcourt

"Billy-Ray Belcourt’s Radical Poetry," The Walrus, June 2018

Film

FUBAR II, 2010, Alliance Films

A Few Items That Were Cut in the Revising Process

“King of the New Canada,” Mordecai Richler, New York Times

https://www.nytimes.com/1985/09/29/magazine/king-of-the-new-canada.html

“Freezing Deaths: The Starlight Tours.”

https://gladue.usask.ca/node/2860

“Pictou County and the Last Spike,” Saltwire

https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/federal-election/pictou-county-and-the-last-spike-82478/

“You’ll Never Believe How Queen Elizabeth’s Corgis Are Fed.”

https://people.com/royals/youll-never-believe-how-queen-elizabeths-corgis-are-fed/

“Prime Minister Harper Denies Colonialism in Canada at G20”

Publications

If you’re in Alberta, or have an out-of-province subscription, you’ll be able to read my latest cover story, “Smith vs. Smith,” in the December issue of Alberta Views.