I could not sleep. My bedroom was silent, the house was silent, and the city outside was also oppressively silent, and these layers of silence were so heavy that they seemed to drown me. Each time I thought my mind was at rest, I felt a spinning motion, as if from too much alcohol, and a sudden wave of nausea came close to overwhelming me, so I had to sit up to steady myself. And then—

“You are not finished seeing,” said a voice in the corner of the room.

My eyes scanned that corner, the darkest part of the room, behind my desk and in front of my closet. The outline of the ghost was very faint, almost as if he had been drawn in pencil onto the wall. It was only when he stepped forward, toward me, that his form emerged as that of a very old, bent-over man, almost a hunchback. Despite his age, his gait was unwavering, steady, and confident. He was coming for me. For the first time since all of these strange incidents had started, I felt scared. The expression on the ghost’s face was very severe, almost vengeful looking, and I thought he intended to hurt me.

“Keep your distance!” I warned him.

He laughed a humourless laugh.

“You think you know a clever trick or two, do you?” he said. “I am aware that in the past you’ve successfully banished sleep paralysis by challenging it outright, as if ready for a duel. But you won’t get rid of me like that. I’m not in your head, nor am I a projection of your body. I’m my own boss. I am the Ghost of Christmas Past. You’ve no choice but to go where I take you.”

He told me to get up. I was so persuaded by the seriousness of his tone and the sinister pose he struck—his finger pointing right at my heart—that I obeyed immediately. “Follow me,” were the next words he spoke. With that, he walked directly toward the wall and out the other side—in other words, into the sky above 105th Street. He disappeared from view. The fear in me grew. If I had not believed in him, I would have gone right back to bed, convinced I’d simply imagined his visit. My fear came from being left behind—of being stuck in my room while he drifted away. I felt I had no choice: I had to walk through the damn wall just as he had.

To my intense surprise, once I had steeled myself for impact, it turned out that walking through the wall was easy. It was like bracing for a punch, and receiving instead a loving caress on the cheek. The wall moved through me like a light lunch. Once out the other side, I saw the Ghost of Christmas Past putting on a great overcoat and then breaking out into a mad dash. I ran in pursuit. We were running in the sky, which should not have been possible, and yet there we were, hurtling upwards until we met the clouds and were swallowed by them.

When we landed, we were in a clearing in the middle of a forest. The smell of moss and lichen and grass was thick. Everywhere the odours of dampness and flourishing life filled the air. In the centre of the clearing, taller than any other tree in the vicinity, there was a huge oak. In front of the oak, a small crowd had gathered. Most prominent among the crowd was a man with a huge axe in his hands. The steadiness of his suspicious gaze upon that tree told me that he intended to do something serious. His eyes glinted from an internal light.

“That trunk is five or six times thicker than the waist of any man I know,” I observed. “Why doesn’t this wild man go cut one of the million other trees?”

“This tree is sacred to the god Thunor, and hence sacred to the local German pagans,” replied the ghost. “They come here and worship it, and it is rumoured they make sacrifices to it—sometimes sacrifices of children. Boniface here is going to cut it down and make a church out of it.”

The first smack of the axe colliding with the tree trunk resounded through the forest. Boniface immediately withdrew the axe and swung again with such ferocity that I thought he would knock himself over, but he miraculously remained rooted firmly on his feet. We watched him hack at that enormous tree until there was an almighty cracking sound. A murmur of astonishment passed through the crowd, which grew in volume to cries of alarm as the great tree teetered and started to swoop downward, and dozens of people standing directly underneath scattered in all directions.

Afterwards, there was a profound silence. What made the entire spectacle so unsettling is that Boniface had not moved from his spot, as if he had been confident all along that the falling tree could not possibly be a threat to him. He had put down the axe and now stood, arms crossed over his chest, looking at the results of his labours. For several minutes he stood so still that he seemed to have fallen into a coma on his feet. No one spoke. Everyone looked to him in expectation of what would happen next. And then finally his limbs loosened, his arms fell to his sides, and he wandered over to a tiny tree, no more than a sapling, and pointed to it. I’d not noticed the tree before. It had been completely overshadowed by the giant oak. Boniface spoke in a voice that was gentle and yet somehow audible all the way at the edge of the clearing, where I stood with the ghost.

“This little tree, a young child of the forest, shall be your holy tree tonight. It is the wood of peace. It is the sign of an endless life, for its leaves are ever green. See how it points upward to heaven. Let this be called the tree of the Christ-child; gather about it, not in the wild wood, but in your own homes; there it will shelter no deeds of blood, but loving gifts and rites of kindness.”

I finally understood why the Ghost of Christmas Past had brought me to this place. That little fir was the first Christmas tree. I wanted to make some kind of declaration about my insight, and was on the verge of speaking, and yet when I turned to the ghost, I saw him gesturing into the darkest reaches of the forest behind us, and then he started running right for it, and I was so terrified of being left alone that I followed him—again.

Now when I say that I followed, I must admit that I lost sight of him almost immediately, and I could see nothing whatsoever, so absolute was the darkness in that forest. It would have been more truthful to say I was in pursuit of a mere notion about the ghost’s whereabouts, running headlong into the void. In a rational world, I would have surely run straight into a branch or a trunk and done serious damage to myself. But this was no rational world.

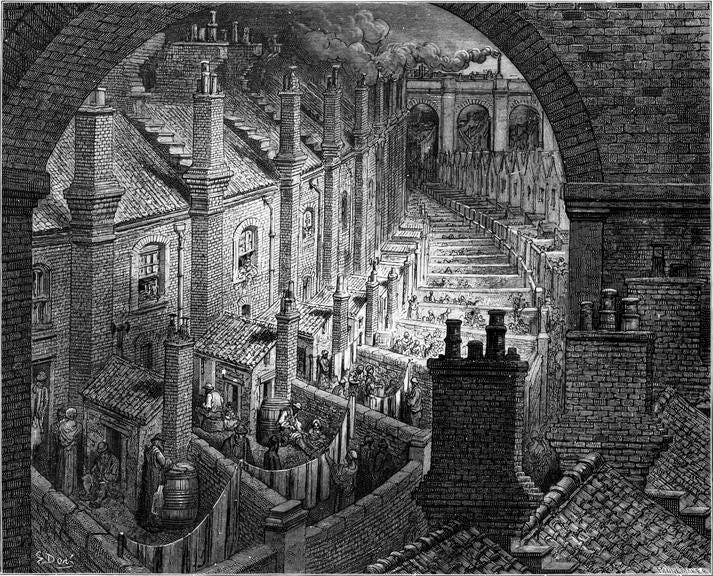

With the next breath I drew, I knew I had left the forest, even though everything around me was still deathly dark. The smell of moss and dampness and flourishing life was gone. The smells that assailed me now were of piss and rotting garbage and smoke and a dozen other terrible, unidentifiable odours. A blast from some kind of deep whistle reverberated through the black night and made the wall of my skull rattle. I looked up to where the sound had emanated and saw a black steam train charging over a huge bridge. Now that I could see the train, I could also see the entire city landscape unfurling around me. I was standing on a brick wall, the ghost a few paces in front of me. A continuous black shadow on one side revealed itself to be an endless row of housing, each back wall giving onto a tiny square yard enclosed by yet more brick walls. In each yard there were people—all shapes and sizes and ages.

In the yard directly below where I stood there was a skirmish between two boys on one side and an older man on the other. The man, draped in a huge blanket, was backing himself into a corner, and the boys were throwing stones and letting loose with wild kicks. The man clung to something under his arm. I couldn’t tell what it was. He shouted that the Lord would judge the boys harshly. The boys laughed. They ran at him. The bigger of the boys landed a punch on the man’s jaw while the other pulled the blanket down. Underneath there was a mere wisp of white fabric over the man’s torso. Convinced that something terrible was about to happen, but completely uncertain as to what, if anything, I was expected to do, I watched the two boys beat the man with their fists. The object in his possession rattled to the ground. Even after the man had keeled over, the boys kept going, kicking him remorselessly. I heard a pathetic yapping and understood that the man had been holding onto a caged dog, but there was nothing the man could do for his dog now—all breath had departed his body.

The boys released the dog and the bigger one held the shivering form to his chest proudly and said, “Let’s call him Devil, ‘cause his owner’s gone to meet his maker and Devil’s on our side now.”

I caught up to the ghost and asked what had compelled him to bring me to such a place to witness such horror. Wasn’t there anything we could have done?

“You’re aware of the grandfather paradox?” asked the ghost.

“No,” I replied.

“We can’t intervene in history,” said the ghost. “They call it the grandfather paradox because if you travelled back in time, and let’s say the bigger of those boys was, in fact, one of your ancestors—let’s say he’s your great, great, great grandfather—and let’s say you intervene to try and save the old man with the dog and by accident you kill the boy, well, now you’ve killed the very person who made it possible for you to be born later down the line. Hence it’s an impossible act.”

“That boy was no ancestor of mine!”

“Sure, sure,” said the ghost. “Your ancestors lived in a nicer part of town, didn’t they?”

With these words, he suddenly shoved me and I lost my footing and fell. I felt my body hurtle down and I expected to violently hit the stone floor of that disgusting yard but when, after a few seconds, my body was still falling, I understood that the ghost had performed another of his tricks of time and space, and that I was in for a gentle landing, which I neither deserved nor wanted.

“I don’t know what gives you the right to barge into someone’s life and do whatever you please!” I shouted. “The first ghost showed me places in history about which I was genuinely curious, but this place—it’s just awful.” All of these words spilled out from my mouth while I was in flight and seemed to fall like pebbles, even faster than my body, and when I heard a sudden clattering sound I thought it was from the impact of the words themselves. I then realized the sound was coming from a new and quite different scene.

There was a small boy whose body was supported by a metal frame, the top part containing a contraption rather like a vice that held up his head, and the bottom part being screwed in on both sides of his waist. His legs were unencumbered and yet he had great difficulty walking without the help of his crutch, which he held tightly in his little fist. He had veered accidentally into a table in the middle of a dimly lit kitchen, knocking over a container of dried peas. That was the clattering sound I had heard earlier. As I looked at his family—his mother and father, Bob Cratchitt and Mrs. Cratchitt, and his brothers and sisters—there was not a look of consternation on any of their faces about the mess the youngest had made. Martha, the eldest sister, simply gathered Tiny Tim into her arms and took him out the door into the adjacent wash house. The ghost insisted that we follow. We saw a large wood-fired oven, and a pudding baking inside, and we watched Tiny Tim helped into a chair by Martha, whereupon he heaved a great sight that stretched his fragile chest outwards, and briefly his eyes closed.

“Is he sleeping?” I asked the ghost.

“Not at all,” said the ghost. “When he wants to take in the odour of a particularly delicious item—Christmas pudding being his favourite—he closes his eyes. You won’t see this scene in the text by Dickens, by the way. I’ve visited the Cratchitts many times, and I know what all the characters are up to when they’re off stage, so to speak.”

“Very clever,” I replied. “Is this touching scene supposed to help me ‘get over’ the brutal murder we saw back in the other part of town?”

The ghost was now wandering out of the wash house, through a tiny alley, where there was a small gate that he unlatched, and in my usual way I followed him, although not without considerable apprehension, as everything about the city outside of the Cratchitts’ residence was grubby and menacing. We walked for a while through narrow streets that trickled haphazardly in all directions, rather like a rabbit warren, and the people, although thin in numbers, were nevertheless seized with purpose, hurrying from little shops—a bakery, the butcher’s, the greengrocer’s—carrying great armfuls of goods into nearby residences, and on the upper floors of several buildings we heard merrymakers already in fine spirits, laughing and clapping.

As we walked, the ghost said the murder of the old man by the two boys was not a scene he had intended for me. We had descended in that place because that particular view, as illustrated later by Gustave Doré, had always impressed him, and he had thought it would similarly impress me, given what it revealed about the immensity, crowdedness, squalor and absolute chaos of Victorian London. Then, well, it was no great surprise there happened to be a crime in progress. There was almost always a crime in progress. When Doré had walked the streets, gathering sketches and notes for his illustrated guide to the city, he had continually been under police protection to ensure his safety.

“I don’t expect it to be a consolation to you,” said the ghost, “but that old man was for many decades caught up in the dog fighting business, and bred a line of highly vicious fighters that caused untold suffering to other dogs. He racked up some debts to nefarious people, didn’t pay, fell on hard times, and was banking everything on that puppy in the cage.”

“You’re right,” I said. “That isn’t any consolation.”

“Ah, we’ve arrived at last!” the ghost suddenly announced. “It’s Old Marley’s former residence, inhabited now, of course, by none other than Ebenezer Scrooge.”

End of Part II

Notes

Historian Roger Pearse cannot find a printed record connecting St. Boniface to the Christmas tree any earlier than the late 19th century. It shows up in a short story by Henry van Dyke called “The Oak of Geismar,” published in Scribner’s Magazine, vol. 10, July-December (1891). The quote attributed to St. Boniface above—“This little tree, a young child of the forest, shall be your holy tree tonight”—was plundered by me from that story. While we do not know if this story of the first Christmas tree is in any way rooted in historical fact, there can be no doubt that it was the Germans that popularized the practice of felling a fir tree, bringing it into the home, and decorating it. Germans introduced the custom to England and to North America, and by the twentieth century it had spread to pretty much all of the nominally Christian places in the world.

Books

Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. Tom Holland, Little Brown. 2019.

A Christmas Carol in Prose: A Ghost Story of Christmas, Charles Dickens. Chapman and Hall of London, 1843. Electronic edition by Top Five Books, 2011.

Doré: Master of Imagination, Edited by Philippe Kaenel. Musée d'Orsay, Flammarion, and National Gallery of Canada, 2014.

Essays and articles

“Why do we have Christmas trees? The surprising history behind this holiday tradition.” National Geographic

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/christmas-tree-customs

St. Boniface and the Christmas Tree

https://www.catholic.com/magazine/online-edition/st-boniface-and-the-christmas-tree

A modern myth: St Boniface and the Christmas Tree

https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/2021/12/06/a-modern-myth-st-boniface-and-the-christmas-tree/