It was 1998, and I had resigned myself to spending most of Christmas Day alone. Around midday, I left my apartment and descended to the sidewalk, walked up to Whyte Avenue and the intersection of 109th Street, and caught a bus downtown. When I arrived on the other side of the North Saskatchewan River, I used several escalators to ascend to the top floor of Edmonton City Centre, and there I met up with a small number of fellow “Christmas orphans,” and we watched the animated movie, The Prince of Egypt.

When the film was over, I wanted to return to my apartment immediately. Thankfully, the Christmas orphans were amenable to my departure and made no complaints. On my return journey, I started to feel anxious—especially during the brief walk from Whyte Avenue to the apartment. I didn't want anyone to know that the large house on the corner would be totally vacant all day except for me, that all the other residents were enjoying their Christmasses with their families elsewhere. I didn’t want pity and most of all I didn’t want some kind of last-minute rescue operation to save me from solitude. I had chosen to spend the day this way. I could have quite happily spent some time in Banff with my parents at their timeshare or at South Cooking Lake with my friend’s family. But both of those options would have obliged me to leave Edmonton and hence give up several days of earnings at the knife store in West Edmonton Mall.

I didn’t feel out of sorts about the situation, although I did feel rather numbed to it. I ascended the stairs to the second-floor apartment, wincing a little at each creaking step, reassuring myself that the worst of my solitary Christmas was over: I had survived the outing, I was back on familiar grounds, I was safe.

Once inside, I ate a large hunk of bread and a big piece of Jarlsberg cheese—not festive fare, but nevertheless, it was the food that I most craved at that moment. Jarlsberg was one of my favourite cheeses, yet I never purchased it for myself as it would have imposed a heavy tax on my modest budget. The cheese was an inheritance from my parents who had, at the last minute, decided to leave it in Edmonton rather than take it to Banff. I also had a bottle of their red Chilean wine, which I had furtively slipped into my backpack just before skipping out of the house with a hearty yet not entirely heart-felt “Merry Christmas!”

After the red wine, the bread and the cheese, I felt tired. I tiptoed away from the kitchen, still trying to be as quiet as a mouse, even though I knew very well that the apartments above mine and below mine were completely empty. I retired to my bed, fully clothed. As I drifted toward sleep, the words to the song, “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas,” sounded out in my mind—although not intrusively. My mind was simply echoing the jingle that I had heard on the PA system at the downtown shopping mall before the screening of The Prince of Egypt.

I’d scarcely completed one rendition of the jingle when I woke up. Standing in the corner of my bedroom was the Ghost of Pre-Christmas of the Very Distant Past. He was the first of the three spirits that visited me that day. This ghost, like the ghosts that were to follow, was strikingly similar in appearance to several professors that I had seen in the hallways of the Humanities Building at the University of Alberta. The ghost was quite stout, and the bottom two buttons of his sweater-vest would have been impossible to fasten over the swell of his stomach. He had a thick, grey beard that, at the very moment that I spotted him, he was stroking thoughtfully with thumb and forefinger.

He called me by my name. I should have been frightened but, to be candid, I had somewhat expected something strange to happen that day, and I felt prepared for him—as prepared as one can ever be for one’s first encounter with a ghost.

“You have some questions about Christmas,” said the ghost. “Do you not?”

“I suppose so,” I replied, rather non-committal about it. The questions had all been unspoken, silent, just like the song “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas,” and the ghost’s power to see the contents of my mind was rather unwelcome to me, as if I’d been spotted undressing or picking my nose.

“Are you wondering whether your choice to keep to yourself means you have strayed from the true meaning of Christmas?” the ghost asked.

I did not answer him, chiefly because I didn’t need to. He knew my thoughts, perhaps better than I did. By this point, I was sitting upright in my bed. I was gaining an appreciation for the ghost’s form, which tended to blur at the edges whenever he gestured with his arm or made any other kind of motion. It was impossible to see right through him—he wasn’t transparent—yet nor was his body solid like mine. It had the watery quality of a mirage, which impaired my ability to fix my eyes on him properly, as if his very form had magical properties that resisted the full capacities of my focus.

Many of the things that happened that day were rather like a visit to a cinema in which the novice projectionist is trying out a lot of different film reels and is struggling to make the picture as clear and steady as it should be. If The Prince of Egypt had been screened so poorly, there might have been a mutiny. I would have been tempted to run into the projectionist’s booth and call out, “For Pete’s sake, get it together, or call in someone with more experience, or else!” Yet, of course, on that day, I never had reason to call out such words, because I was always in the company of a ghost with a natural authority that I trusted.

The ghost announced that he was taking me to ancient Rome. Yet when he took me, I don’t mean to say he grabbed my hand and wrenched me out of my bedroom and flew up with me into the sky to circumnavigate the globe, or any other such comical stunts. Allow me to again use the analogy of the film reel. He waved his arm, and suddenly that appendage became a huge shadow that fell across the room and threw everything into darkness, as if the cinema lights had been extinguished. As these things happened, the ghost explained to me what was going on.

“Your education has been sufficient to tell you that Christmas has a precursor, and now you will see it for yourself,” he told me. “Behold, we are in Rome!”

With these words, I was suddenly floating over a city, but so rapidly and in such an imprecise fashion—rather like tumbling around, doing somersaults in space—that it was impossible to gain an overall impression of the totality. I did see the Temple of Vesta, with its eternal fire burning, the smoke rising from the dome and merging with the murky clouds. I also gained an appreciation for the hilliness and for the perfect geometry of the architecture of its central areas, and yet we did not linger long over these parts. We came to a halt in the open doorway of a large tenement block on the city’s outskirts, and I became conscious of the other nearly identical buildings on that street, and of the huge numbers of people that were inside—behind me—and outside, thronging in the evening shadows.

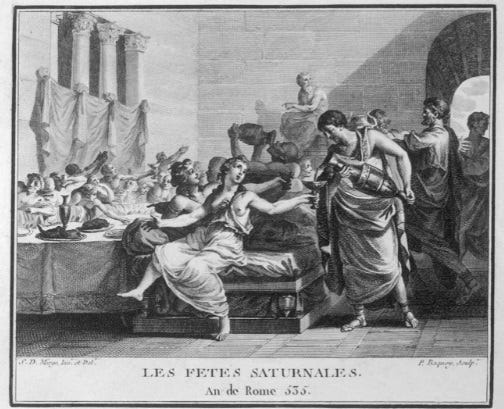

It was the first day of Saturnalia, explained the ghost. The usual order of ancient Rome had been completely disrupted. We saw several young, rather frightened girls—clearly serving girls or even slaves—being transported in a four-poster, canopied litter, carried by four, very elegantly and brightly dressed men. The men were very evidently of the noble classes. They were laughing and calling out to one another as they tried to navigate their way under an archway at the end of the street, and I suspect that they were all very drunk, as they failed miserably and the litter teetered over and fell onto its side, and the girls jumped out. One of them fell and seemed winded while the other landed with more elegance and immediately ran away.

When I turned to look at the home behind me, I saw about a dozen children sitting at the table, one of them wearing a laurel wreath that had fallen down over one of his eyes, and all of these children were being served by adults, who were bowing and showing them great reverence as they brought in huge platters of cold meats and shining fruit.

Saturnalia, the ghost explained, was held in honour of the god of agriculture, Saturn, who had once been the ruler of the very first inhabitants of Italy, long before the rise of the Empire. Saturn’s reign had been a golden era, during which no one was a slave, there was no private property, and all things were common to all. Just as the ghost was explaining this, a new crowd of revelers suddenly appeared on the street, and if we had not jumped out of the way, they would surely have surely trampled us as they called out “io Saturnalia!” and charged into the home where the children were.

“It’s like this all over Rome?” I asked the ghost.

“Yes,” he nodded. “And in many other parts of the Empire.”

“It’s total madness!” I exclaimed. “How long do they keep going with such wild behavior?”

“Oh, for several days,” replied the ghost. “During the Republic, it was seven days. Under Augustus, it was three days. No one works. No official business can be conducted. As you can see, it’s a decadent affair, with gift-giving and gambling and excessive drinking—so it’s not without certain costs. Augustus felt obliged to rein it in a little.”

“The Christians are not going to like it,” I declared.

“Ah, let us investigate that proposition,” the ghost replied, and he waved his arm again, and it was as if a drape had fallen over my eyes, and the next thing I knew, I was hurtling through a heavy darkness. My body was again convulsed by a series of apparent somersaults. I tried opening and closing my eyes, but this made no difference to my ability to see, and so eventually I kept them closed. All this commotion should have made me nauseous, but by some miraculous power, it did not.

We alighted in the Great Palace of Constantinople, in an enormous hall whose walls were covered in mosaic of such detail that it was impossible for me to appreciate anything except a small fraction of the illustrations—the only one I recall depicted a proud looking charioteer in pursuit of a second chariot. As I have already mentioned, my ability to see was perpetually being disrupted, and moreover, all the sudden jump cuts were dizzying, and I had glimpses at a great deal more than I actually saw.

As I tried to steady myself, I noticed that at the far end of the hall there was a throne, upon which a middle aged man sat quite primly and properly, wearing a brown tunic with large and billowing sleeves, decorated on the shoulders with gold and crimson ornamentation. This man, who I understood immediately to be someone of great importance, was studying a large scroll on his lap. At a distance from the man on the throne, but evidently in conversation with him, was a group of more plainly dressed men attired mainly in dark browns, some of them in black. The atmosphere of studiousness and seriousness in that hall, even though it was concentrated in just that distant corner, had diffused across the entire vastness of space.

"We are at the court of Emperor Theodosius I," explained the ghost, in a whisper. "He and his religious advisors are preparing a decree."

“Looks like hard work,” I said. ‘What’s the decree all about?”

“Tightening the screws on paganism,” said the ghost. “Theodosius has already proclaimed Christianity to be the official religion of Constantinople, and by extension, the eastern and western parts of the Empire, although among we historians there is considerable debate about how far into the lives of ordinary people beyond this city his influence was felt, especially early on. The decree he is working on today seeks to repress pagan rituals, including the offering of wine or incense to pagan gods, the suspending of wreaths in tribute to the spirits of one's own household, the divining of entrails—even tying ribbons around a tree. All of these are punishable offenses.”

“I see,” I said.

“You should read Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” recommended the ghost. “Gibbon argues that this decree is ‘the only example of the total extirpation of any ancient and popular superstition,’ and is therefore ‘a singular event in the history of the human mind.’”

“So what about Saturnalia?”

“Saturnalia is on the way out,” said the ghost. “Yet the Roman traditions prove difficult to entirely eliminate. Many of the struggles of the next centuries are between pious Christians on one side and more practical Christians who seek to make accommodations with the customs of the past. The excesses of Saturnalia, as you know, have their contemporary analogues, and only a total fanatic would seek to deprive ordinary people of the pleasures of the winter season.”

“Very true!” I agreed, and I turned back to the throne, where Theodosius was making a great show of standing up. A hush fell over the group of men. Theodosius descended from the throne, which was suspended above the floor by the height of about two feet, and he very gracefully gave the scroll to one of his advisors, who in return made a small bow of respect, turned away, and walked very quickly out of the hall through a huge set of gold-inlaid doors.

“It is done,” said the ghost. “It is time I took you home.”

End of Part I

Thank You!

Thank you for being a subscriber. I hope you’ve enjoyed the bracing embrace of the cephalopod! If you appreciate the free content from the Substack Octopus, consider clicking one of the SHARE buttons, enter the email address of a friend, enemy, or family member, and encourage that person to join the octopuses!

Notes

Justinus: Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories - Book 43

"Pompeius Trogus lived in the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus. He wrote a Universal History, which he called "Historiae Philippicae", consisting of 44 books. He is unusual amongst Latin authors in putting more emphasis on external history than on Roman history. Trogus' history has not survived, but we do have a paraphrase of it, written about 200 years later by someone called M. Junianius Justinus." It is Justinus that we can thank for a description of the reign of Saturn.

Who Was Caesar Augustus?

https://www.learnreligions.com/caesar-augustus-first-roman-emperor-701063

“Christmas and the Roman Saturnalia,” Jennie M. Churco, The Classical Outlook, Vol. 16, No. 3 (December, 1938)

“Saturnalia: the origins of the debauched Roman 'Christmas,’” History Extra

https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/how-did-the-romans-celebrate-christmas/

Martin of Braga, Bishop (c.520–79).

https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100137261

“The End of Paganism,” James Grout, hosted by the University of Chicago

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/greece/paganism/paganism.html

Great Palace of Constantinople

https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/great-palace

Publications

My feature article about labour versus the government, “Smith vs Smith,” is online this month at Alberta Views.

Yes! I’m so excited for this, thank you Laurence. Dare I hope this is an advent series complete with visiting Christmas Ghosts providing guided tours of different historical periods that have influenced the way we celebrate Christmas today?