My father, who became a literary scholar after an earlier, unsuccessful career in music, discovered Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” while he was a mature student at the University of Stirling, Scotland. I conducted an interview with him in 2020, a year before his death, and he recited a verse from the poem without difficulty, which surprised me, because Parkinson’s disease had made many of his other memories rather incoherent.

One of his earliest and published papers, “Guilt and Death: The Predicament of the Ancient Mariner,” takes the reader to unexpected places—notably, Hiroshima. My father wrote that our era has multiplied the chances of sudden, unanticipated catastrophe. It’s the era of the road accident, the derailment, the bomb—the nuclear bomb in particular, bringing complete destruction and mass death, with after-effects lingering for decades, even centuries. “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” with its arbitrariness and infinite cruelty, is a poem that anticipates the spirit of our age.

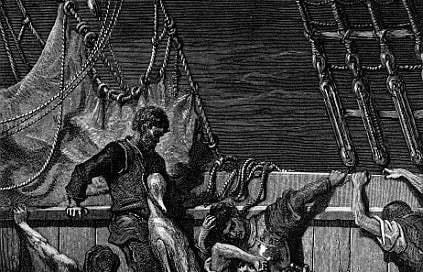

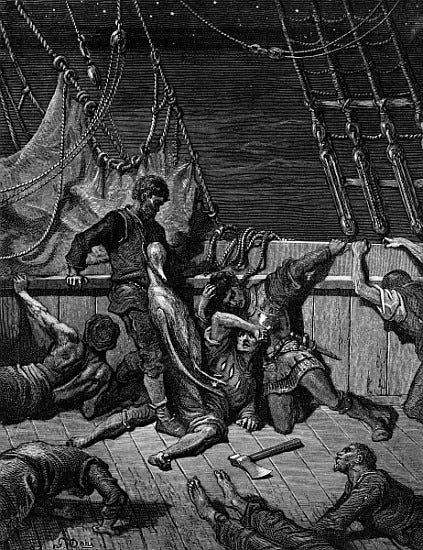

The Mariner is stuck in the moment of his deepest suffering, driven forward in the ship alone by spirits that torment him, judge him, and seek to instruct him. One of Coleridge's contemporary readers complained that the poem had no moral. Coleridge responded that “it ought to have had no more moral” than the tale of “The Merchant and the Genie” in Arabian Nights.

The Mariner's plight is one of stasis and passivity. The world acts on him. He is capable only of bearing witness and telling others what he suffered. My father cited Robert Jay Lifton's book, Death in Life, about the psychological effects of the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima, and he included in his essay a survivor’s description of a destroyed school and “one dead child lying there and another who seemed to be crawling over him in order to run away, both of them burned to blackness.” Survivors of Hiroshima repeated stories of suffering like this, seemingly trapped in their memories, struggling to comprehend their experiences.

I followed in my father’s footsteps and read Lifton’s Death in Life, just as he had decades previously. I also went back to a different book, the first one in which I had encountered the physical and psychological suffering of the atomic bomb’s survivors. It was Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory. She had included a detail about melting eyeballs. It was dismayingly gruesome. I had to be sure I hadn’t misremembered it. The detail was from the chapter “Doomsday Pattern,” in which Gabbert reflects on her own memory of this horrific detail, which she remembers encountering while a junior high school student. She successfully locates it in the book where she first found it, Hiroshima by John Hershey:

“When he penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about twenty men, and they were all in the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks.”

The decision to drop the atomic bomb was not based solely on the sheer killing power of the new weapon. The conventional bombing already underway was devastating enough. It was the aesthetic value of the mushroom cloud that would terrify the enemy. It was the horrifying and supernatural aspect of the bomb that would convince the enemy to surrender. This western interpretation of events is rendered by Laurens Van Der Post, who was a prisoner of war in Japan at the time of the explosions.

“This cataclysm would end the war, and a new phase of life would inevitably result from it. This cataclysm I was certain would make the Japanese feel that they could now withdraw from the war without dishonour, because it would strike them, as it had us in the silence of our prison night, as something supernatural. They, too, could not help seeing it as an act of God more than an act of man, a Divine intimation that they had to follow and to obey in all its implications.” Laurens Van Der Post, The Night of the New Moon

Naturally it had not escaped my father’s notice that Death in Life was a perfect inversion of the words Life-in-Death, the spectre that visits the Mariner’s ship and curses him to go on living forever, even as two hundred of his shipmates are struck dead. To many survivors of Hiroshima, to go on living was a gift that, if given the choice, they might well have refused.

The first bomb fell in the early morning, as locals were having breakfast, getting dressed, hurrying out to work. “Neither past experience nor immediate perceptions—the two sources of prior imagination—could encompass all that was about to occur,” Lifton writes. A B-29, called the “Superfortress,” approached the city, causing an air raid siren to be set off, but when the plane turned away, the all-clear signal gave locals the false impression that the danger had passed. That first B-29 was a weather plane, and its departure was a signal, unbeknownst to the Japanese, that the catastrophe was still to come.

The details of the disaster are fragmentary, almost incoherent (the following is from Lifton’s interview with a survivor):

A blinding

Flash cut sharply across the sky

The skin over my body felt a burning heat

A blank in time

Dead silence

And then

A huge boom

The initial explosion destroyed sixty thousand buildings. The bomb devastated almost everything for over three thousand metres (two miles) in all directions. People were knocked over, thrown around, pinned under debris, knocked unconscious. The survivors that saw the infamous mushroom cloud were awed by it. “A monstrous mushroom with the lower part as its stem—it would be more accurate to call it the tail of a tornado,” recalled one survivor. “Beneath it more and more boiling clouds erupted and unfolded sideways… The shape… the color... the light… were continuously shifting and changing.”

The chaos and confusion of these early moments resist narrativization. There is a beginning—a starting point of the terror, yes—but no end. One survivor, coming to his senses in his destroyed home, describes moans and screams all around him, but feels powerless to do anything. “I felt I was going to suffocate and then die, without knowing exactly what happened to me,” he told Lifton.

A thirteen-year-old schoolgirl, horribly burned, was dismayed that her teachers could no longer take responsibility for their students. Teachers were jumping into the river to alleviate the suffering caused by their burning. “Since we had always looked up to our teachers, we wanted to ask them for help. But the teachers themselves had been wounded and were suffering the same pain we were.” The girl, like her teachers, jumped into the river.

There hangs over the survivors the long shadow of guilt. Children describe the pain of losing their parents, but why had they suffered such terrible losses when they themselves had done nothing wrong? To be orphaned was a punishment, but who had done the punishing?

A woman described to Lifton the slow and agonizing death of her daughter from the effects of radiation, concluding: “I thought it was very cruel that my daughter, who had nothing to do with the war, had to be killed this way.”

“There were dead bodies everywhere,” an electrician told Lifton. “At that time, I couldn’t figure out the reason why all these people were suffering, or what illness it was that had struck them down… There was no light at all, and we were just like sleepwalkers.” After the catastrophe, there wasn’t wild panic but “ghastly stillness.”

Lifton borrows from Dr. Hachiya’s Hiroshima Diary, which contains a description of survivors walking like automatons away from the devastated city centre and toward the suburbs in the hills—an “exodus of a people who walked in the realm of dreams.”

The eyes of the dead or dying victims were unbearable to the survivors, who trudged on with the unpleasant and arduous task of living. I again thought of the Mariner’s plight as the sole survivor among his ship’s crew.

An orphan's curse would drag to hell

A spirit from on high;

But oh! more horrible than that

Is the curse in a dead man's eye!

A Hiroshima history professor described his attempts to find his family, walking past the dead and the injured. He had no time for pity. “They looked at me and knew that I was stronger than they… The eyes—the emptiness, the helpless expression—were something I will never forget… They looked at me with great expectation, staring through me.”

The film, Oppenheimer, refuses to show a single Japanese survivor of either the Hiroshima or Nagasaki bombings. There is just one scene in which the bomb’s physical effects are represented. It’s at Los Alamos, when Oppenheimer gives a rousing speech to those who have been working for many months to be ready for the famous Trinity test. The viewer is supposed to receive flashes of insight into Oppenheimer’s feelings of guilt as the applauding audience starts to disintegrate into the visual trickery of the film’s special effects. We understand the spectral audience members are projections of Oppenheimer’s imagination. They’ve all been victims of radiation—they’re burned, they’re sick, they’re vomiting. But they’re all Americans, like Oppenheimer, and so we’re witnesses simply to the tortured conscience of a scientist, and yet spared the sight of the suffering he and President Harry Truman have unleashed.

“Few Americans have ever fully grappled with the enormous devastation of the atomic bombings,” writes Don Carleton for the Japanese Times. Carleton notes that photos from both of the bombed cities were suppressed by the Japanese military and subsequently by the occupying American forces. It is only recently that these photos have become available in the West, but only to those bothering to look for them. “Americans are still looking at the history of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from a distance — visually, emotionally and intellectually,” he writes.

From the first nuclear catastrophe, which ushered in one epoch—the so-called peace of the post-war period—to the next great catastrophe, Chernobyl, which ushered in a very different epoch, very few lessons were learned.

Vasily Ignatenko was one of the first firefighters on the scene of the explosion. When he was hospitalised, a friend of his wife, Lyudmilla, advised that he be given lots of milk. “But he doesn’t drink milk,” Lyudmilla replied. “Well, he will now,” the friend replied. Lyudmilla bought all the milk she could—enough for her husband and his fellow firefighters. It did no good. “They kept losing consciousness all the time… For some reason, the doctors kept insisting they’d been poisoned by gas, no one said anything about radiation.”

Svetlana Alexievich’s Chernobyl Prayer, upon which Craig Mazin’s HBO series was based, is the result of thousands of hours of interviews conducted with Chernobyl survivors. The enormity and mysteriousness of the catastrophe are rendered, not like a complete picture, but rather like the fragments of a shattered mirror. Right from the opening interview with Lyudmilla, whose story is perhaps the most moving of them all, the chaos and absolute amorality of Chernobyl unfold for the reader with a gathering, accumulating array of overwhelming details. While Lyudmilla’s beloved husband was dying in agony, their baby was inside her, taking the brunt of all the radiation she was exposed to, effectively saving her life.

At Chernobyl, many of the survivors of the accident had lived through the horrors of World War II. They used war as their reference point to try and understand Chernobyl, but such comparisons proved inadequate. It was not war, even if at times it mimicked war’s patterns, with the mass mobilisation of troops, the tanks, the evacuations.

The documentary, “Chernobyl: The Lost Tapes,” first screened on Britain’s Sky TV in February 2022. It strips away all of the conventional devices of narrative to bring the viewer even closer to the tragedy. In the video footage captured in the immediate aftermath, post-disaster Pripyat—the workers’ town adjacent to Chernobyl—is illuminated by cheerful sunlight, just like on any other fine day. This ordinariness is dismaying for the viewer, as it was for local inhabitants. Invisible, odourless radiation contaminates everything. The world itself becomes suspect. The world itself deceives us.

During my initial preoccupation with Chernobyl, I embarked on a Google tour of some of the salient facts of the disaster. The cloud of radiation had spread over a vast distance. I discovered that the worst-hit town in Poland, northwest of Chernobyl by 980 kilometres, was Olsztyn, the very town in which my wife was born. I read a New York Times article about a Polish woman named Maria, also born in Olsztyn, who had taken up residence in the United States in 2004, living a normal, happy life until suddenly contracting thyroid disease. It turned out that the rates of thyroid disease had sharply increased in Olsztyn since Chernobyl. In that town there are now entire hospital wings devoted to trying to treat it.

We had spent part of our honeymoon in Olsztyn. Troubled by the information I shared with her, my wife called her parents and her older sister. Did they remember Chernobyl? Yes, they did. They remembered being given iodine pills by the authorities and being told that there was nothing to worry about. They remembered eating food grown in the garden without giving a second thought to any potential risk.

We were worried. My wife had suffered from numerous respiratory ailments as a child. Maybe those ailments were a precursor to something more serious. And something strange had happened one day in Two Hills, Alberta. My wife had been shadowing a speech pathologist as he went about his day’s work—she was curious about speech pathology as a possible career—and so the speech pathologist showed her how he conducted his examinations. He discovered what he thought was an irregularity in the way she spoke, as if her throat were constricted. “You should get that checked out,” he said. Once we were back in Montreal, where we were living at the time, she arranged for an ultrasound. The results were transmitted to the family doctor. The ultrasound showed what appeared to be a very small lump in her throat.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit shortly afterwards, and we had more immediate worries. It wasn’t until a good year later, by which time we were living in Edmonton, that my wife scheduled another ultrasound. The doctor was French, and had practised in Quebec for a while before moving west. When he saw the Quebec ultrasound next to the new ultrasound, he laughed.

“You know what’s happened here? The equipment they used is cheap and outdated. The image isn’t high enough resolution. The image is just grainy. That’s why it looks like there’s a lump. There’s nothing to worry about, your thyroid is fine!”

To imagine Chernobyl capable of following my wife over three decades to another continent had given me some inkling of the incredible magnitude of the disaster. Yet I was merely an inch closer to understanding why it had seemed so vital to follow my father from the Ancient Mariner to two of the twentieth century’s greatest nuclear catastrophes and to keep writing about these and related issues over and over again for a manuscript that, in many respects, became increasingly unfocused the more I worked at it.

“If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb, when it comes, find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs,” wrote C.S. Lewis. Very sane and reasonable.

I thought back to the origin of my inquiry—to my feelings of surprise and disorientation as I saw my father visibly haunted by Coleridge’s poem. I re-read his essay, “Guilt and Death,” and the poem that inspired it. I read three separate biographies of Coleridge, as well as academic papers, and a book about the “original mariner,” a real-life Englishman from Oxfordshire who shot a black albatross in the South Seas in 1719, an account that came to the attention of William Wordsworth who conveyed the story to Coleridge. But the longer I remained in this mode, the more trapped I felt. There was a labyrinthine path my mind was following that continually seemed to be leading me back in on myself.

My father’s explanation for the arbitrariness of the Mariner’s plight was that Coleridge’s sudden loss of his father when he was a young boy had caused a lasting trauma, a trauma that Coleridge himself was never able to properly acknowledge or understand. Citing the work of a psychiatrist writing in the 1960s, my father argued that children of a certain age believe their thoughts have the power to cause external events to happen. And so if a child is orphaned before gaining greater maturity—“the years from six to nine are the most dangerous for bereavement” my father wrote—the child believes it’s their fault. Their thoughts made the terrible tragedy happen. Because the child has done such a terrible thing, they will be punished over and over again, for all their mortal days. The inexplicable dread and guilt that preyed on Coleridge, which shows up in “Mariner,” was a result of his childhood bereavement, my father argued.

Although he wouldn’t say so in “Guilt and Death,” my father had a personal reason to be invested in this particular interpretation. He, like Coleridge, had been bereaved as a young boy. His eldest brother, a pilot in the Royal Air Force, was killed in southwest England during a training flight in 1954. That loss had thrown the entire family into such deep grief that to speak the brother’s name afterwards became verboten.

And I, too, had been bereaved as a boy. I lost my mother. Worse, she had killed herself, a fact that was dangerous to discuss.

For most of the summer, I set aside all of these ideas and the associated readings, and then eventually, just as the sunflowers in our local back alleys were drooping, I went back to my research and my lifeless manuscript, just to see if I could mine my previous work and unearth just a small artifact worthy of consideration—something new. Finally, my erratic way of searching eventually led me to an aphorism by Franz Kafka.

This aphorism was new to me, and I had uncovered it by accident. A friend and I were corresponding about an earlier draft of this essay, and he helped me find the aphorism where I first remembered hearing a fragment of it: in a sermon by the late American pastor Timothy Keller.

I kept on reading. I found out that between 1917 and 1918, Kafka wrote over a hundred aphorisms from the Bohemian village of Zürau. This was the only stage of Kafka’s life when he was able to devote himself full-time to his writing. He had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and granted a medical leave from his job in Prague. The aphorisms are among his least well known works. A recently published English translation contains the aphorism that first caught my attention through Keller.

"We are sinners, not only because we have eaten from the Tree of Knowledge, but also because we have not yet eaten from the Tree of Life. The state in which we find ourselves is sinful, quite independent of guilt." Aphorism No. 83

Keller had used just the second part for his sermon—“we find ourselves sinful, independent of guilt,” which omitted a few of the words I found in the full aphorism, but the more surprising omission was the previous sentence about the Tree of Life.

To say we have not yet eaten from the Tree of Life—the sly insertion of yet—astonished me. We know that access to this tree was forfeited by Adam and Eve because they ate the fruit of the other tree, of Knowledge. And yet Kafka invites us to think of the Tree of Life as ahead, in the future, rather than behind us in a distant past.

The morning before discovering this aphorism, I had become supremely irritated when I discovered that I had left the power cord for my work laptop back at the downtown office, and yet I needed it in order to work from home that day. I have a tendency to get disproportionately worked up about such blunders. “Great! Now I have to drive all the way downtown and then drive all the way home again, just for the sake of a stupid cord!” But I did it, and when I finally had my cord in my hand and was walking back to my car, which was illegally parked in a lot on Jasper Avenue, I noticed that the heavy clouds over the river valley were letting in brilliant rays of sunlight. The view momentarily pulled me away from all my prior irritations, obsessions, fears and doubts. I was glad. My heart was softened, rendered more receptive to the aphorism I was about to receive.

The scholar Walter A. Strauss described Kafka's plight like this: “The awareness of sin is our summons to self-judgement.” Kakfa’s twisting and turning paths always go back to the self, and to self-judgement. After a while, it feels suffocating and airless.

My father knew that it is possible to sometimes find a way out of this labyrinth. Leave the house, leave the city. Go for a walk. In the 1990’s, he had been co-editor of a CD-Rom for which he had retraced the steps of the Romantic poets’ most striking walks—whether in the Lake District or in Sicily or the French, Swiss or German Alps. In the final interview I conducted with him, he told me that Coleridge responded to his walks in a way that was “animistic.”

“It’s the idea that every bird and rock and stone has a life of its own,” my father said. “If you see a bird flying along, how do you know it's not getting a view of Paradise?”

I went back to Coleridge’s poem. It seems more important to me now than it did before that Coleridge situated the Mariner’s crime in seas that no one had ever entered. As sailors used to say, “Below 40 degrees south there is no law; below 50 degrees south there is no God." In this so-called godless place, the albatross started to follow the ship. Coleridge is very intentional about the sequencing of this scene. Prior to the entry of the albatross into the poem, there is no animal life at all, only the sailors and the ice.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

It is not impossible to imagine the profound uneasiness that the sailors would have experienced in the absence of all other forms of life, hearing the strange sounds of the ice, seeing the seemingly endless desolation of the seascape, wondering about the mystery of the ship’s trajectory. Then, briefly, some relief:

At length did cross an Albatross,

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God's name.

Yet the Mariner killed the bird. Why? Coleridge will not provide a reason. Suddenly the ship’s crew enter a nightmare of an origin that makes no sense and from which there appears to be no escape.

It is not impossible to imagine that after the destruction brought by Oppenheimer’s bomb, the blasted landscape would have struck the survivors as a nightmare on earth, as if they had entered territory that no humans were supposed to enter, or territory meant only for humans responsible for the most unspeakable of crimes. In the bomb there was a force that had previously only been wielded by the gods, or God, a force capable of wiping out civilizations, of definitively ending an era. To wander the ruined streets in the wake of such a force was to live like a ghost. What could interrupt or disrupt such a brutal feeling of abandonment and despair?

Some of us are in search of the force that would deliver us from such a fate. What we want is a power that—however fleetingly or enduringly—propels us beyond the death in life.

Notes

I've decided to include most of my sources here. I prefer this over hyperlinks in the body text.

First a note about the Kafka aphorism. I read two different English translations of aphorism 83, and the second did not contain the particular choice of words that I found so arresting—"not yet eaten from the Tree of Life" was instead "we didn’t eat from the Tree of Life." I don't read German and so I cannot puzzle my way through the original. Maybe the differences are important or maybe not.

I watched Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer in the movie theatre in the first month after its release. I supplemented my viewing with a few readings, notably, this rather remarkable speech by Oppenheimer himself.

It is a less well known fact of history that the uranium used in the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was mined on Dene territory in the country that is conventionally called Canada. The Dene did not know what the uranium would be used for, and once the truth finally became clear to them, they sent a delegation to Japan to issue a formal apology.

Books discussed:

Chernobyl Prayer, Svetlana Alexievich

Death in Life, Robert Jay Lifton

The Unreality of Memory, Elissa Gabbert

The Zürau Aphorisms (editor Reiner Stach, translated by Shelley Frisch)

Essays and articles:

"Franz Kafka: Between the Paradise and the Labyrinth," Walter A. Strauss, Michigan State University Press

“'Barbenheimer' highlights U.S. ignorance of nuclear reality,” The Japan Times

“Chernobyl's Lingering Scars,” Joe Nocera, New York Times

“On Living in an Atomic Age,” C.S. Lewis

“Canada’s Uranium Highway: Victims and Perpetrators,” Cape Breton Spectator

“Guilt and Death: The Predicament of the Ancient Mariner,” David Miall, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900

Recent publications

In the last few months I’ve published about education and education and Liverpool Football Club. If ever I’ve got publications worth pointing you towards, I’ll always note them here in this discrete section.

Thanks for reading

This was the first installment of “The Substack Octopus.” More installments will come out at the rate of about one per month, which, according to all the advice I’ve seen, is not nearly enough to achieve any kind of success. So be it. Not all the posts will be as long as this one, but they will always be 2,000 words or more—an attempt to make up for the infrequency and to give you value for money. I hope you will stick with me and encourage all your friends and family, and even distant acquaintances—even people you do not very much admire—to do likewise. Let them enjoy the bracing embrace of the cephalopod!