My daughter has been given a Chromebook to use at school. This moment in parenting, like many others, came so much faster than I had expected. She is seven!

In the before-times (Before Chromebook), we were helping her prepare for a spelling test, drilling the words us, use, out, our, and about. In the mornings we would read stories about dogs and rabbits, Métis culture, bike rides, or the adventures of Gerald and Piggie, etc. She has an active imagination. Sometimes she pretends to be an Arctic fox, climbs into a large cardboard box and calls it her home.

Now we live in the after-times (After Chromebook), all the above is still true, except now she is also expected to create and remember a password for her personal computer profile — just like me, just like any other boring old adult. I am sure many parents see this as an exciting rite of passage, like the first time their kids get the keys to the car. But I am uneasy.

I remember how shocking it felt to discover that children were just another marketing demographic — just like adults, in other words. I discovered this when I was myself a child and lacked the words to understand what was happening to me. My family and I had gone to live in Illinois for a year and, for the first time, I had a television of my own. On Saturday mornings, I was able to watch cartoons like He-Man. During the commercial breaks I was harangued by the toy company cartel to buy figurines of impossibly muscular men and bimbo-princesses and replicas of the Millennium Falcon. From my current-day perspective, it’s striking to remember the regressiveness of the American media. How much darkness was permitted to entice and ensnare children through that little black box. Back home in England, none of this was permitted — no GI Joes, big-busted women or the constant cartoon violence. On the BBC, the presenters of Blue Peter would teach you how to make a banana pudding or explain how to recognize Orion in the night sky. In the paternalistic mother country, childhood was a time to engage in learning and discovery and you were mostly protected from the adult world while in this phase of formation. In America, you were protected from nothing. You were to be force-fed infotainment (at best) just like any other market segment, while doing your best to avoid kidnappings or murder. (In the very apartment block we lived in, a woman fatally used a gun on her kids, her husband, and, lastly, herself.) An American kid had to assume almost all the same responsibilities as an adult, just in “fun” size.

Because of this past, I have become, perhaps, unduly apprehensive about the fragility of childhood and I have a hard time “going with the flow” with whatever are the accepted norms of the moment. At the same time, I don’t want my kids to be home-schooled and cosseted or totally out of step with their peers. Yes, they can watch Creature Cases. No, they cannot have an iPad. Yet one is forced to concede that a parent only exerts so much control. Ultimately a child is a product of the era they grow up in. And children of this era get Chromebooks!

Before recently getting a new job, I was entertaining the idea of writing another education story, this time about technology in the classroom. I had, in fact, pitched the idea to a magazine for whom I’ve written before. The editor politely declined. It was not the right moment, he said. And then, because of the demands of the new job, I just dropped the idea. But I can’t let go of the impulse that led to my pitch. Do people care that kids get Chromebooks at the age of seven? I have a feeling that it’s not generally considered a worthwhile political subject. And yet, I’ve gleaned enough of Marshall McLuhan to sense that, in fact, the age at which kids get Chromebooks will likely emerge in a decade or two as one of the most important facts of our current era — far more consequential than being acquainted with the current provincial minister of education and the latest reforms he’s introduced to the school system with scarcely a thought for the impact on actual, ehem, children.

It’s all very well to say, computers are an essential tool in contemporary society so children should learn to use them, but note that nobody is handing a seven-year-old the key to a Honda Civic. I’ve now been reading Jonathan Haidt’s Substack for long enough to have developed an instinctive skepticism about all of this. All of it!

Technology, sitting so close to its elder, science, has dodged the scrutiny it deserves because it comes with a whole lot of built-in biases about its own worthiness and yet, dangerously, grows from the same revered Tree of Knowledge as its parent discipline. Why would you do something as archaic as arithmetic when you can spare your brain cells and have a calculator do the work for you? Yet science remains the superior perspective to bring to these conversations. It feels quite urgent to point out at this juncture that the use of technology in the classroom is an unproven pedagogical approach. That is to say: there is no reputable, rigorous study available today that says digital technology has a beneficial impact on student learning. Meanwhile, there are very big and powerful companies that have every reason to promote and sell technology while evading the cold eye of scientific scrutiny.

For computers to deliver on their purported emancipatory, innovative and creative potential, the majority of humans would have to approach computers with this thought in mind: “I have an interesting problem or a personal project with which I need some assistance from a technological tool.” The problem or project would precede the use of the tool. But this is not at all how computers are used by most people today. Most people use computers because they literally have no other choice. In this respect, computers have become a lot like cars. If you design a city in which it's almost impossible, or at least highly inconvenient, to get from A to B without a car, lo and behold, the majority of citizens will buy a car. If you design a society in which almost all personal and work functions require the intermediary of a computer, lo and behold, computers will become ubiquitous. But this isn't a matter of choice or personal creativity or “unleashing” some kind of inner potential. This is simply a matter of necessity.

A few snapshots of the increasingly contested terrain:

“In May of 2023, schools minister Lotta Edholm announced that Swedish classrooms would aim to significantly reduce student-facing digital technology and embrace more traditional practices like reading hardcopy books and taking handwritten notes. The announcement was met with disbelief among pundits and the wider international public: why would an entire country willingly forgo those digital technologies which are widely touted to be the future of education?” Jared Cooney Horvath.

J-Pal, a global research centre based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, looked at 126 research studies on technology in the classroom and concluded that “initiatives that expand access to computers…do not improve K-12 grades and test scores." J-Pal also found that "online courses lower student academic achievement compared to in-person courses."

There are a host of other studies we could examine here, including the most comprehensive of them all — UNESCO’s landmark report in 2023, a survey of education globally, which concluded “there is little robust evidence on digital technology's added value in education.” What most interests me is the why. Why is technology in the classroom not very useful?

What is a computer for? The ubiquitous word “tool” is typically employed at moments like these. A computer is a technological tool. OK, but what is it for? Clearly, a computer is not like a hammer. Anyone with even the most rudimentary understanding of hammers understands that hammers have a specific function — you use them to drive home nails. The use of hammers can be broadened beyond that, but not by very much. Even a far more sophisticated tool — an MRI machine — has a fairly narrow set of applications, yet with quite broad implications for the field of medicine. Of course, computers factor in here: data from MRI machines will be crunched by computers in order to see patterns.

Yet the computer itself — in the hands of a student — what is that for? (I am asking the question broadly, sidestepping the particular cases of children who need computers for accessibility or similar reasons.) When exposed to rigorous scrutiny, the answer to the question starts to become clearer. Computers are primarily for multitasking and distraction. Jared Cooney Horvath’s essay, quoted above, is very strong on this point, observing that, according to a 2019 American survey among children aged 8 to 18, digital technologies are primarily being used for video games, watching TV or film clips, social media, and listening to music. In terms of minutes spent on a weekly basis, these are far and away the most popular uses of digital technology (for example, 10 hours per week for TV and film, versus one hour and 14 minutes on reading for pleasure). Perhaps this will come as no surprise. Intrigued, I looked at the survey itself to learn more.

At a granular level, the survey shows that the creative capacity of digital technologies is hardly being used at all. “Content creation” of all kinds is a fringe pursuit. For example, creating digital art or graphics was an activity that only 10% of respondents said they enjoyed, and those who enjoyed it devoted an average of one hour and 14 minutes per week to the activity. How about writing? Only 1% of the eight to twelve-year-olds in the study used digital technologies for writing, while among thirteen to eighteen-year-olds the rate was 5%. How about coding? Remember when it was all the rage to teach everyone to code? Only 3% of the younger age cohort spent any time in the week coding, a rate that was even lower for the older age cohort at 2%. Horvath extrapolates from this study and concludes that during a typical U.S. school year of 36 weeks, students will spend 198 hours using digital devices for learning and 2,028 hours for consuming media.

The problem with the computer specifically is that, tethered to the internet, it has become an everything device. What is a computer for? Almost anything. And that’s the very problem.

In a different study, published in 2013 in the journal, Computers in Human Behavior, also cited by Horvath, when the behaviors of middle school, high school and university students were closely monitored, students lasted only an average of six minutes on their assigned homework task before switching to a different activity — usually social media. There is a lot to be said about the limits and potential of the human attention span. In considering the implications of this study, Horvath doesn’t mince words. He asks us to imagine a group of people asked to learn about buoyancy with help from a jug of beer. There is no doubt that the jug of beer is well suited to this research experiment, which will have great potential impact for learning. Yet depending on the willpower of the people in the cohort, there is an obvious danger here, and I don’t think I need to point out what that danger is.

As a tool primarily of multitasking and distraction, there are serious consequences for students in scaling up the use of digital technology. It’s as if we had given them a drug even more intoxicating than beer and then said, “Now go learn with this!” What vexes me most is that children are being distracted by videos and gifs and pictures of their friends at the exact moment in development when they are at their most curious and creative. Assign a child a truly engaging educational activity and it can hold their attention for hours.

“Even before digital devices took over the classroom, students struggled with lack of attention, shallow thinking, overconfidence, and other learning problems,” writes Horvath. “However, with digital devices, the frequency of these problems increases.”

Alberta’s education system is the one I know the best. Here the government has become obsessed with assessment. This, too, is part of the culture of the computer. Under the UCP government, the number of standardized tests taken by elementary students has increased threefold. The new schedule of testing starts from kindergarten, and a child could take as many as 32 standardized tests by the time they leave elementary school. Previously they would have taken a maximum of ten tests.

In my eldest daughter’s first month of Grade 1, her teacher told me, “I don’t have as much time as I’d like for individualized instruction because I’m too busy administering the new numeracy tests.”

Literacy and numeracy tests at these early grade levels are carried out with prompts from the computer to the teacher. Data is collected in real time so that Alberta Education knows exactly what is going on. However, these assessment tests are purportedly “formative.” That is to say, they are not intended to be a performance measure of the student or the school. They are meant to assess how the student is doing so that, if needed, extra supports can be provided.

But there is no correlation between the assessment scores and extra supports provided. The students can score poorly or superbly or somewhere in between and there is no doubt that, given the current budget allocations, it’ll make little difference in the quality or the quantity of support given. Schools are stressed to the limit.

There are, however, serious implications for the teacher’s time. In 2018, the Alberta Teachers’ Association sent a survey to teachers and school leaders across the province, gathering responses from 644 participants. Among the most important findings: "Teachers reported the digital reporting tools increased teacher workload, parental expectations regarding the frequency of reporting, and the amount of time required to track and report student progress." This is before the massive scale up of assessment at the early grade levels. It would be interesting to see the same survey repeated today.

My suspicion is that the government is very happy with the current state of affairs. The leading interventions to improve educational outcomes would be the very interventions they have steadfastly resisted for half a decade: hire more teachers, reduce classroom overcrowding, and cut the bureaucratic burdens, making it possible for every teacher to spend more time with individual students. But this kind of educational intervention is not popular with the Alberta government, because it’s not novel, it’s not “innovative.” Keeping everyone busy with computers, endlessly producing reams of fresh data, is a perfect state of affairs for our government, because it gives them a form of direct control over an increasing portion of teachers’ time and gives them a bunch of numbers that allows them to mutter important-sounding words like “accountability” and “achievement” and “outcomes” etc. What isn’t happening is any noticeable improvement in learning.

Computers are not inherently coercive. But the way they’re deployed at scale, the coercive element has become the most prominent. If the government truly had magnanimous reasons for insisting that students at the early grades be assessed for numeracy and literacy and for schools to identify students that need extra supports, they could easily give that broad direction and leave it to the discretion of teachers and school leaders to get the job done. It’s the use of computers and the collection of data through use of the internet that makes the assessment coercive. No one asked for these tests — not teachers, nor students. And almost no one in the schools believes they’re actually doing any good.

This is symptomatic of a broader problem. If you believe that computers and other digital tools are the answer to some kind of problem, you have, in effect, answered a question that no one was asking. When I talked at length to the education professor who was going to be my initial source of information for the magazine article that was never written, he told me about PowerSchool. It’s an online information system that allows students and parents to see information about grades, attendance records, fees, etc. Introducing PowerSchool has put pressure on teachers to populate the platform with data. Every minute spent feeding the machine is a minute not spent with students.

We have arrived at a strange moment. Students and teachers use computers routinely because there is a widespread societal belief that everyone should use computers routinely. But until we come up with a vision for why computers should be deployed in schools, students and teachers will be stuck on a treadmill to nowhere.

NOTES

Just as a I was wrapping up this post, I found out that Google has set up many of its Chromebooks to become obsolete prematurely. Consider this story:

“This fall, tens of thousands of kids will head back to school with Chromebooks that are about to be useless.

It’s not because the laptops are broken. Perfectly good computers are getting thrown away because Google has set arbitrary “death dates” for Chromebooks — often just a few years from when they were purchased — after which Google no longer provides software support.”

“Why parents, teachers and school districts are fed up with their Chromebooks”

This reinforces the point I was making at the top of my essay, which perhaps seemed a little idiosyncratic: the tendency of American corporations to see children as simply another marketing demographic — another market segment. Their drive is to make childhood, and education, profitable for them. It’s a very base impulse, and one that I think K-12 education systems everywhere should vociferously resist.

Hope everyone out there is weathering the storm of Trump 2.0.

Vive le Canada libre!

Articles, etc.

“The EdTech Revolution Has Failed,” Jared Cooney Hovrath

“Technology in Education: A Tool on Whose Terms?” Global Education Monitoring Report, UNESCO, 2023 https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385723/PDF/385723eng.pdf.multi

“Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying,” Larry D. Rosen, L. Mark Carrier, Nancy A. Cheever, Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 29, Issue 3, May 2013, Pages 948-958 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563212003305

Research Study of Digital Reporting, Assessment and Portfolio Tools: Results Summary, Alberta Teachers Association, 2018

https://teachers.ab.ca/sites/default/files/2024-09/coor-101-15_digital_reporting_assessment_and_portfolio_tools_2020.pdf

New Screening Assessments, Alberta Government

https://www.alberta.ca/early-years-assessments#

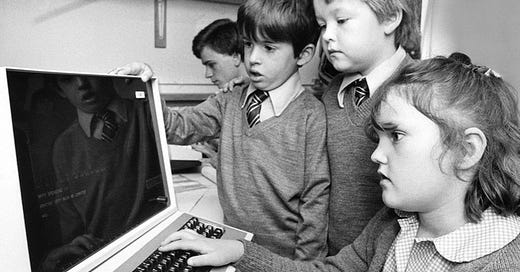

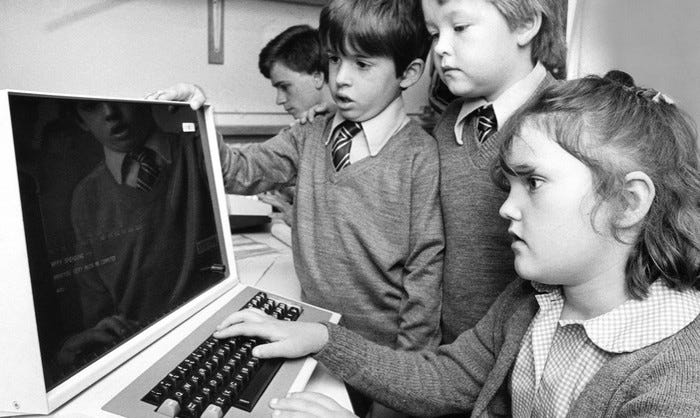

Photo

A brave new world: the 1980s home computer boom, History Extra. February 24, 2016

https://lab.cccb.org/en/connective-nightmare-at-the-call-centre/