I’ve been reading A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe. Not long ago there was a small revival of general interest in Defoe’s journal as well as the diary of his approximate contemporary, Samuel Pepys. In April 2020, just as COVID-19 was becoming a global crisis, Forbes published an article called “Now Is The Perfect Time To Read Samuel Pepys’ Diary From 1665.” The same month, The Conversation published “Defoe’s account of the Great Plague of 1665 has startling parallels with today.”

Almost four years later, on the cusp of 2024, it’s an even better time to read such texts. Hindsight has been instructive. It’s easier to discern the arch of the pandemic’s progression and subsequent retreat, and so to compare it to past crises. (I’ll leave aside the question as to whether COVID-19 is “over”.)

In 2020, when Jesse Brown of Canadaland talked to Margaret Atwood for one of his “Isolation Interviews,” he perhaps hoped to tap into a kind of prescience that had helped Canada’s most famous author write the Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood’s response to COVID-19 was indicative of a far broader yearning among self-styled progressives during those early months. “Let's think of it as a reset button,” she said. “It gives us some time to think of what kind of world we want to live in after the other side of this...” She named a few things that she believed might change in the post-pandemic era, and then, almost as a sidenote, opined: “The anti-vaxxers will surely shortly be a thing of the past.”

There was no such yearning or optimism on evidence from the author of The Elementary Particles, Michel Houellebecq. “I don’t believe for even half a second statements like ‘After this, nothing will ever be the same.’” he told France Inter. “On the contrary, everything will remain exactly the same...We will not wake up, after our confinement ends, into a new world. It will be the same, but a bit worse.”

There was an enormous appetite for the post-pandemic world to return to the same state as the pre-pandemic world. Perhaps nowhere was that appetite greater than among the business class. So what had once seemed almost unthinkable is now our everyday reality: it’s as if the pandemic never happened. We went from talking about it every single day, in almost a ritualistic fashion (Prime Minister Trudeau’s pandemic media conferences took place at the same time each day—81 times over 110 days in total) to generally avoiding the subject altogether, unless to share some kind of old grievance or old trauma. As of today, we inhabit the world Houellebecq could foresee, and the one that perhaps history told us would eventually become our destination.

In 1665, a group of rowdy revelers used to congregate every day at the Pie Tavern in the parish of Aldgate, London. They would drink and carry on late into the night, typically sitting close to the windows that overlooked the street, that is to say, Houndsditch. This vantage point gave them a view of the dead-carts that frequently trundled toward the pit that had been dug at St. Botolph’s, the parish church. It was easy to know when the dead-cart was coming because it was custom for the driver to ring a bell quite aggressively. Thereupon the revelers at the Pie Tavern would open the windows and jeer and mock the passersby, utterly unsympathetic to their grief and lamentations. This went on for month after month of that terrible plague year. As the narrator of Defoe’s journal tells us, the “master and mistress of the house grew first ashamed and then terrified at them.”

We learn from Defoe’s so-called journal that one night the narrator gains entry to the churchyard at St. Botolph’s because he knows the sexton. He is there purely out of curiosity, a reason the sexton initially finds uncompelling, but the narrator seems a fairly determined fellow, and so the sexton eventually relents, telling him that what he’s about to witness will probably be as good as any sermon. “It may be the best that ever you heard in your life,” he says.

Sure enough, it’s not long before the dead-cart trundles along, bringing a small delivery of dead bodies and a smaller number of living souls—the driver and the buriers. At first, these are the only people the narrator sees. Then he realizes there is another man that has come to the terrible, yawning pit. It’s a man who has lost his wife and several of his children. The man wears a large brown cloak, underneath which his hands are tearing at his body, as if he is suffering from some unbearable kind of agony. The buriers gather around him cautiously. They have become accustomed to the sight of people, mad with grief or from the infection itself, who throw themselves headfirst into the pit to join the dead. But this man doesn’t attempt to do anything quite so rash. He tells the buriers that he simply wants to watch his family be laid to rest and then he will leave quietly. And so the buriers let him alone, and the man is calm for a while. Then the man sees what the work of burying the dead actually means: the buriers haul the dead bodies into the pit, shovel a few spadefuls of dirt over the top, and that is all. The bereaved man cries out and falls down, and no one quite knows what to do with him. Someone eventually has the idea of taking him to Pie Tavern, where he might be known to the local people and perhaps someone will attend to him.

At the Pie Tavern, the usual crowd of revelers are completely drunk. It is one o’clock in the morning. The revelers first turn their attention to the master and mistress of the house, furious that they allowed the grief-stricken man inside, but then they turn upon the man himself, mocking and ridiculing him. Some of them ask the man why he lacked the courage to toss himself into the pit after his family. What’s wrong with him? The man can hardly breathe a word in the face of such callous indifference. He sits in abject, miserable silence. The narrator finds him there and tries to intervene on his behalf, accosting the revelers. How can they be so impudent and even outright blasphemous? But the revelers, unmoved by the grief-stricken man, are hardly in the mood to soften their hearts. They turn their ire toward the new target. They mock the narrator relentlessly, asking him what he is doing outside of his grave. Why is he not at home, praying? The narrator gives up. It is a futile cause.

“These things, I say, lay upon my mind, and I went home very much grieved and oppressed with the horror of these men’s wickedness, and to think that anything could be so vile, so hardened, and notoriously wicked as to insult God, and His servants, and His worship in such a manner, and at such a time as this was, when He had, as it were, His sword drawn in His hand on purpose to take vengeance not on them only, but on the whole nation.”

Of all the dark words I encountered in A Journal of the Plague Year, these struck me as the darkest. The narrator, trying to appeal to the better angels among those revelers, ends up completely disgusted.

By the ghastly light of 1665, contemporary realities aren’t quite so surprising. When death comes to a city indiscriminately, it overwhelms some, it humbles others, and for others death becomes so banal it’s as if it doesn’t exist—it’s just a joke or a major inconvenience. What doesn’t happen is the forging of solidarity, a collective pride of purpose, a great new social project. None of the above. I remember a slightly different version of myself, lying in bed in our rather decrepit Montreal apartment, listening to Margaret Atwood and hoping she would turn out to be correct, and that vaccinations would become incredibly important to everyone, and how a great many other social ills might also be remedied—the isolation of seniors, the health risks of overcrowded, low-income lodgings, the mounting burdens on hospital workers, the anxiety of children, whether in class or on Zoom, unable to truly connect to the overtaxed teacher or even to each other—and none of these ills is any closer to some kind of lasting amelioration. It was Houellebecq, that miserable misanthrope, who had the most accurate of all the literary takes.

I started the pandemic in Montreal and ended it in Edmonton, and during a good deal of that time I was grieving, because my father was dying—not of COVID, but of a pre-existing condition. Yet I felt compelled to try and remain as outwardly optimistic as possible, because I was introducing my daughter to a new city. I had dramatically curtailed my work hours thanks to a severance, so I had a lot of time on my hands to entertain her. My wife did not yet have her driver’s license, and so I used to drop her off at her place of employment, and then embark on some kind of adventure with my daughter—the very best ones being at Fort Edmonton Park, within the city limits, or at Jurassic Forest, in the prairie beyond. Online personalities were my steadfast companions during those long hours when my daughter was asleep in the back of the car. She needed naps of at least an hour, sometimes more. Once I was absolutely certain she was deep in slumber, I would pull over somewhere—any nondescript parking lot would do—and I’d connect my phone to the car speakers, and I’d listen to people talking, the wisest of them being Matt Christman.

The beginning and end of Matt Christman’s Cush Vlog, in which he talked to his audience in long, rambling and digressionary monologues—totally uninterrupted by his usual interlocutors on the more popular Chapo Trap House—forms the bookends of my experience of the pandemic. It first came online in the spring of 2020 and it wrapped up last fall, when Christman, while awaiting the delivery of his firstborn, had a medical emergency from which, by all accounts, he has not yet recovered.

Other men were spending hours in the company of Joe Rogan, Alex Jones or any number of other online personalities. My hours were given over to Christman. There is a peculiar power enjoyed by online personalities who forge deep connections with online audiences. The power can’t be ascribed to the quality of the content, because if it’s quality you’re after, the long-form rambling of all of these men won’t reliably provide it. It’s less to do with quality and more the opportunity to experience contemporary events with these men as guiding companions. In Christman’s particular case, there was a great deal of quality too, yet stretched out like an enormous, baggy sweater that appears utterly formless until you’ve inhabited it for a while.

In our household, we referred to Christman as “the man who fell off his chair.” There was one particular episode during which he was holding forth with great seriousness on a certain topic when some mechanism in his office chair abruptly broke and he went careening into space, off camera, and he had to clamber back, red-faced, find a new chair, and compose himself, aware that he had just created content that would absolutely delight his haters. When I was watching it in the corner of the living room, I laughed so hard I almost choked on my tongue and so, of course, I had to show my wife and daughter.

In the darkest hours of the pandemic, the yearning for some kind of positive social change was surely the result of a dissatisfaction with the pre-pandemic status quo. We did not want to go back to that world. Earlier that year, a billion mammals had perished in catastrophic forest fires across Australia. In Canada, railways from coast to coast had been blockaded by protesters in solidarity with the Wetʼsuwetʼen First Nation in British Columbia, and whether one’s sympathies were with them or against them, there was a sense that our politics had reached an impasse. Not to mention the fact that Trump was president. And then COVID-19 came along. Suddenly it was the primary moving force. Every politician had to have answers to totally new questions. When the Bernie Sanders campaign fizzled out, many people felt bereft because there was no obvious leader upon whom we could pin our hopes and dreams. It was in this context that Christman launched the Cush Vlog, encouraging everyone to take the “grill pill.”

To take the grill pill was to reject both delusion and nihilism, log off, and find footholds of meaning in friendship, comradeship and the simple pleasures of being alive. Staring at screens and owning people online made alienation worse, but having a barbeque — that was a start. (Alexander Zaitchik, Truthdig)

Obviously this was not a manifestation of startling brilliance, rather a humane response to the heightened emotional state of many people at that time. It was advice that a person could actually follow, without being prescriptive. Nevertheless, Christman’s approach to the radically shrinking window of possibility in politics could be intuited: grasp on to any real-world, in-person, tangible action that offers a genuine prospect for making things better, which would almost definitely mean addressing a local—not national or global—challenge.

A desire for a better world, even when shared with large numbers of other people, does not, by itself, change the world one iota. Christman would return over and over again to the simple fact that society-wide transformations occur through necessity. Whenever he logged on, swigged a sparkling beverage from a can, burped, scanned the comments that his fans were posting, he was very aware that the vast majority of his audience members were still far too comfortable to make sacrifices in their everday lives, join with others, and take the risks necessary to make significant change happen. But forces would likely some day disrupt that basic comfort, and then reality might well become very different. “Necessity cuts through the miasma,” he said in February of last year, “but is also very terrifying. It means abandoning all of the comforting layers of responsibility and authority that we depend on.”

It has become rather obvious to say that the pandemic accelerated pre-existing trends (toward more digitization, more social isolation, more accumulation of wealth among the already wealthy, etc.) and it’s also become rather obvious to say that it revealed a lot about how humans behave under duress, but few people have offered practical advice about how to respond in our private lives to the post-pandemic reality of things becoming, each year, just “a bit worse.” We can compare our lot to those for whom reality has become catastrophically worse (Ukrainians, Israelis, Palestinians, and so on) and say, well, at least things are not nearly as bad as that for me. Yet still a gnawing unease won’t go away. Disaster is already swallowing up vast swathes of the world. To borrow from Teju Cole, who borrowed in turn from William Gibson, the disaster is not yet fully distributed. A bit worse and a bit worse and a bit worse will gather weight over time to mean a lot worse. And for this, I feel the need to be ready. There can be no final reckoning with fate while leering and jeering from the confines of the Pie Tavern.

Notes

There are again some straggling items from the last post, or rather, more of an overall explanation I feel I owe readers. Because I have chosen to forego links in the main body of each post, preferring to stow them away in this “notes” section, I’m not being quite as clear as I want to be and perhaps unintentionally muddying my meaning and my methods. In the final part of “Most Wonderful Time,” there were two instances of speech that were not written by me. The first was the short exchange between Scrooge and the philanthropists. They were taken verbatim from A Christmas Carol. The other quote was from the executive director of the Downtown Business Association of Edmonton, which I found in a news story. I do include all of my sources in the notes section, yet from here on, I think it would be a better practice to acknowledge anything that’s borrowed directly from one of those sources, especially if it’s not obvious in the main part of the text. In this particular instance, people who choose to read that far would then understand that the Christmas tree did indeed disappear from Edmonton’s Churchill Square in 2022. I wasn’t making that up.

Now on to more interesting marginalia. I feel compelled to note in passing that A Journal of the Plague Year is not in the strictest sense of the word a journal, although it intentionally takes that form. Daniel Defoe was five years old when the plague was ravaging his city. He waited many years to write the “journal” that is attibuted to “HF,” a person who works in the saddlery business. I’ve read some accounts that call the journal a “literary hoax.” Whatever Defoe’s intention, his methods are impressive. He went back to a major historical event of his childhood and researched the contemporary developments—for example, the publication of the weekly death tolls by the local parishes, and the issuing of various emergency orders, such as sequestration and bans on feasting and other large gatherings, the deployment of “watchmen” to ensure that infected persons or families didn’t try to escape from their homes, and so on—and out of all this he constructed a story about the plague year that holds up as one of the most accurate and rigorous. There are numerous parallels from London’s plague year to the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, one finds that almost all the counter-measures adopted were the same ones that would again be used globally in 2020 and 2021, with the exception of the vaccinations, which were not within the reach of seventeenth century medicine. If anyone thinks people behaved particularly badly in the 21st century, the experience of 1665 will change your mind. Among many other great horrors, a small selection of which is provided above, there are also accounts of infected people attacking and killing their watchmen in order to escape confinement, and there were nurses, who were supposed to care for the sick, who instead suffocated their patients by pressing wet cloths on their faces, and last but not least, it was practically expected that the bodies of the dead would be ransacked for jewellery and clothing—anything of value.

Books

A Journal of the Plague Year, Daniel Defoe, 1722

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/376/376-h/376-h.htm

Images

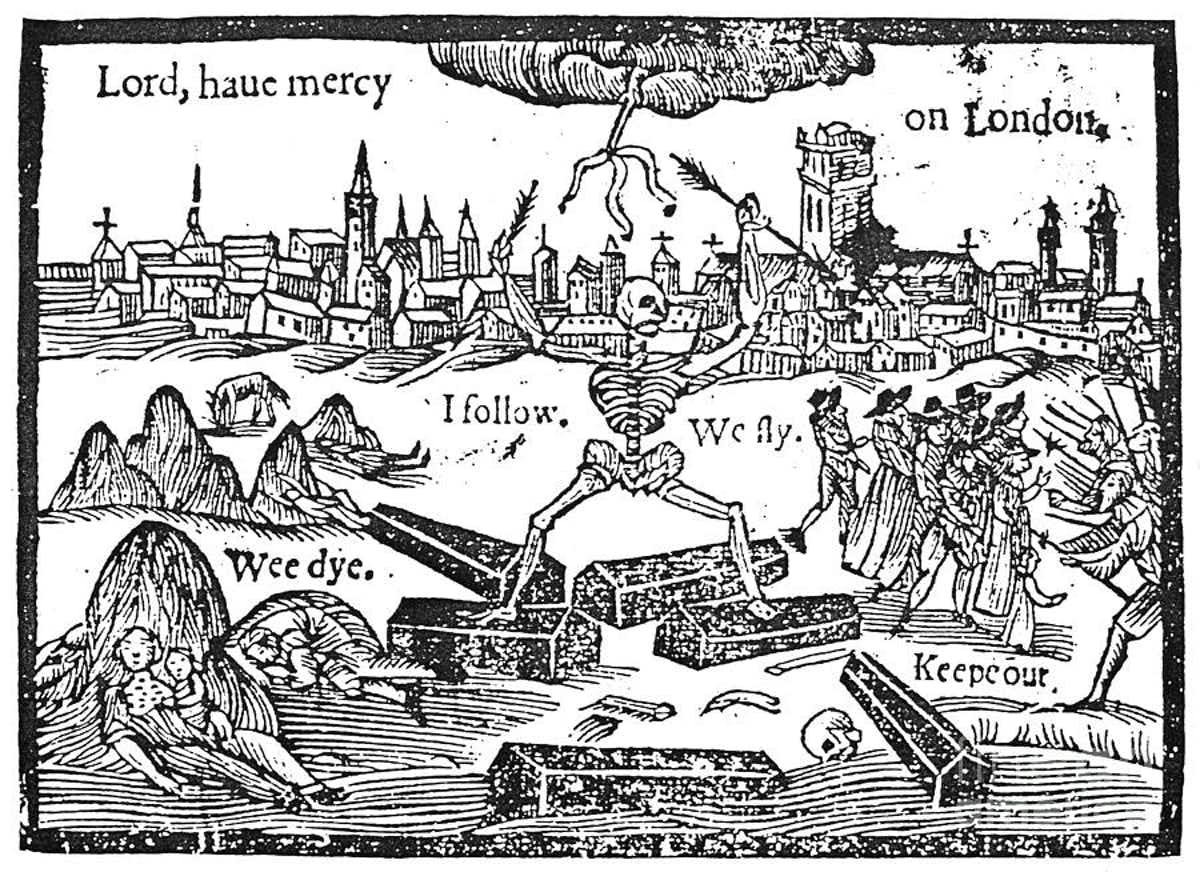

Black Death in London. Artist unknown

The Great Plague of London in 1665. The last major outbreak of the bubonic plague in England.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_plague_of_london-1665.jpg

The Flagellants Attempt to Repel the Black Death, 1349

http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/flagellants.htm

Essays, articles, podcasts

“Isolation Interview: Margaret Atwood.” Canadaland.

https://www.canadaland.com/podcast/isolation-interview-margaret-atwood/

“World will be same but worse after 'banal' virus, says Houellebecq.” France 24

https://www.france24.com/en/20200504-world-will-be-same-but-worse-after-banal-virus-says-houellebecq

« Je ne crois pas aux déclarations du genre « rien ne sera plus jamais comme avant » - Michel Houellebecq.

“Houellebecq: A Bit Worse”

https://newmodels.io/editorial/issue-2/a-bit-worse-houellebecq-transl-kelse

“110 days. 81 addresses to the nation. What PM Trudeau's COVID-19 messaging reveals”

“Plagues of the Past.” Harvard University, Science in the News

https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/special-edition-on-infectious-disease/2014/plagues-of-the-past/

St Botolph's Aldgate, A Journal of the Plague Year, Daniel Defoe

“Blue Guide London, Daniel Defoe and the Plague Year”

https://www.blueguides.com/blue-guide-london-daniel-defoe-and-the-plague-year/

“Now Is The Perfect Time To Read Samuel Pepys’ Diary From 1665,” FORBES, April 30, 2020

“Coronavirus: Defoe’s account of the Great Plague of 1665 has startling parallels with today,” The Conversation, April 6, 2020

“The Grill Master of Acid Marxism: A well-wishing appreciation of Matt Christman”

https://www.truthdig.com/articles/the-grill-master-of-acid-marxism/

“In Defense of Art in Troubled Times.” Teju Cole, Art Basel.

https://www.artbasel.com/news/a-defense-of-art-in-troubled-times?lang=en